ACER author Coral Campbell speaks with The Sector about the value of STEM in ECEC

The Sector recently spoke with author and academic, Coral Campbell, about the value of STEM in early childhood education and care (ECEC), and her perspectives on weaving STEM into everyday learning.

Ms Campbell’s conversation comes about as the result of a recent Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER) publication, which showcases high-quality, peer-reviewed research in education, health, social care, child safety, science, mathematics and the arts into everyday practice for early childhood education and care.

Edited by Anna Kilderry, Associate Professor of Education (Early Childhood), and Bridie Raban, Honorary Professorial Fellow, Strong Foundations: Evidence informing practice in early childhood education and care contains 22 chapters by 34 contributors from 13 universities and institutions around Australia.

Each chapter highlights reciprocal relationships between research and practice and explores guiding principles around key content to support early childhood educators’ learning. Core content knowledge addresses the five Learning Outcomes of the Early Years Learning Framework together with the seven National Quality Standard quality areas.

Given the high volume of discussion about science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) learning in the early years, we spoke with Ms Campbell, to gather her thoughts on how educators can “see the STEM” in children’s everyday activities and enhance their use of inquiry-based STEM language to scaffold children’s understanding of the concepts.

Top tips

To begin our discussion, we asked Coral how educators can start to look for STEM learning in activities and play already happening in children’s days, and build on these moments to meaningfully embed learning.

“Some play themes occur regularly in EC and have strong STEM, so finding out what these are can arm the teacher to be prepared,” she replied.

For example, over any given year, children will be interested in the weather, construction activities and, usually space travel. The recurring topics provide teachers with time to prepare materials.

Looking at common play can also lead to identifying STEM. “Rolling down a hill involves experiences in physics related to force, gravity, friction. Also maths in terms of spatial relations. A teacher can use this play experience to talk with a child about how their body feels as it moves,” Coral explained.

Linking everyday language with STEM concepts and knowledge is another important tip, she said. If a teacher identifies that children are ‘mixing’ mud pies, the everyday word ‘mixing’ links with very early concepts of chemistry.

Shadows, she added, are all about stopping the direct line of the sun or light source. Using the language of STEM, teachers can look past the play and see the learning in play experiences. Children may then explore light, and what happens when light is reshaped or refracted.

Building your own personal STEM knowledge, as an educator, is a powerful tip, which then helps children to see STEM opportunities. This knowledge can be built by undertaking professional learning, working with colleagues or self-educating using online professional learning networks, readings, videos, or discussions with STEM-based professionals.

Finally, talking with children about what they are doing, seeing or experiencing can often highlight moments where children are interested in learning more, or exploring STEM concepts in a way they may previously not have considered.

Using STEM to respond to children’s curiosity

We asked Coral to give an example of how inquiry based STEM language might be used to respond to children’s questions or curiosities.

“An inquiry cycle,” she responded, “suggests five possible processes: Ask, investigate, create, discuss and reflect, and each of these phases might have a child asking a question.”

“A child might ask where a snail lives, or what it eats. Rather than answering outright, educators might build on the question by asking another, such as “what have you seen snails do?” or “how could we find out?”

Both of those educator responses build on the child’s skills of observation and encourage the child to consider their own thoughts, and work with the educator to scaffold learning.

In a second example, Coral shared the process which happened after a shared reading of children’s book Wombat Stew.

After the reading, two children approached their educator to share that they were going to make their own stew.

The educator replied enthusiastically (affirming the validity of their plan and focusing their investigation), ‘What a good idea. What will you do first?’

The children replied that they were going to collect some ‘leaves and gum nuts and feathers and mud’. The educator commented (affirming the validity of their plan and extending their thinking), ‘They are interesting objects to collect. What will you put them in as you collect them?’

Each line of questioning and response allowed the children to scaffold their own learning, and to consider themselves as powerful drivers of understanding.

Changing educator mindsets on STEM

Marylin Fleer’s Conceptual Playworlds research has shown that many educators do not feel confident in their own STEM capabilities and understandings.

We asked Coral how educators might empower themselves to change that mindset?

“Early childhood STEM is not about providing ‘correct’ STEM answers to a child but is more about helping children find answers out for themselves,” she replied.

“Once educators realise that they don’t have to have an answer, they can help a child undertake their own investigation. Understanding the inquiry cycle and the types of question to ask, will encourage the child to make the decisions and undertake their own explorations.”

While experienced educators already know a lot of STEM, she continued, they may not feel confident in planning a STEM experience.

In order to push through this, Coral suggests that the STEM experience “should come from the child or children’s interests. There are many online ‘lessons’ which an educator can follow in the first instance, to help them feel comfortable.”

Making time for STEM

In a day of learning which can, at times, feel crowded, we asked Coral for her suggestions on making time for STEM each day.

Some educators do like to plan STEM to ensure they ‘cover’ it, she explained. If they do this, it should arise from children’s known interests. Common interests for children are plants, dinosaurs, construction activities or pets.

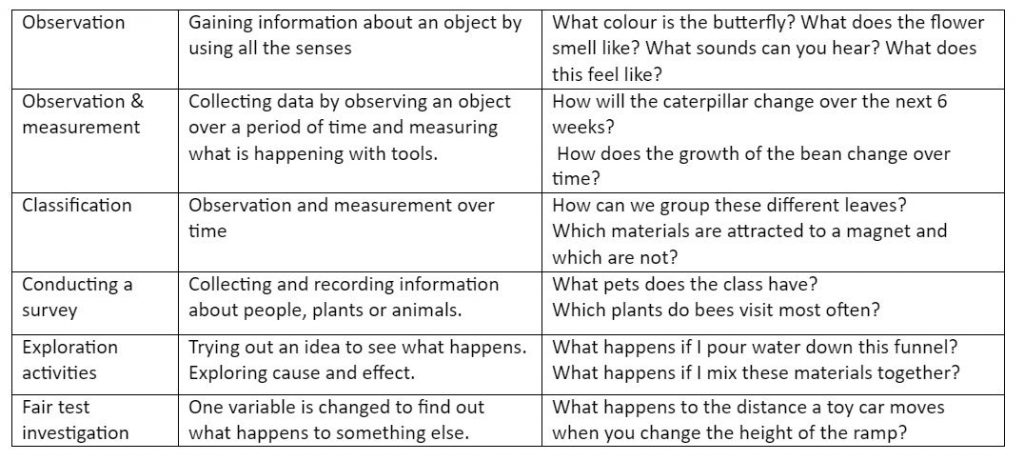

There are some great inquiry activities aligned with these. Some simple questions, arising from children’s own interests could be the stimulus for future inquiries.

For example:

Resources of note

To round out our discussion, we asked Coral to share some of the resources she recommends for those who are just beginning their journey of early learning and STEM, or who simply want to learn more.

As well as the ARDOCH Foundation, which provide the Curious Young Minds STEM Literacy Program that she developed as a supported volunteer program free to kinders, Coral recommends the following books:

Strong Foundations: Evidence informing practice in early childhood education and care

Science in Early Childhood 4 th Edition

Investigating mathematics, science and technology in early childhood

Educators and leaders seeking further support are welcome to email Coral, who can be reached at [email protected]

Coral Campbell is an expert contributor to Strong Foundations: Evidence informing practice in early childhood education and care by Anna Kilderry and Bridie Raban (ACER Press).

Popular

Quality

Practice

Provider

Research

ECEC in focus - Una Springwood’s intergenerational initiative brings young and old together through connection and care

2025-06-30 10:00:45

by Contributed Content

Provider

Practice

Quality

Research

Aboriginal Education Strategy drives early learning and school success in South Australia

2025-07-01 09:55:12

by Fiona Alston

Workforce

Policy

Quality

Research

Inclusive Practice Framework set to strengthen inclusion in early childhood settings

2025-06-24 11:37:00

by Isabella Southwell