Integrated child and family centres overcome fragmented service delivery

One of the biggest challenges for people who most need social services is navigating a fragmented service system. Here we explore one potential solution, integrated child and family centres which ensure that children and families get what they need, where they need it.

Seven-year-old Jake was first referred to an integrated child and family centre (ICFC), The Benevolent Society’s Cairns Early Years Centre, by a paediatrician who had identified that Jake may be living with a disability. Centre staff visited Jake’s mother, Liz, who herself has an intellectual disability. As a result, they were invited to attend the Explorer group at the centre, designed for children experiencing development delays.

Liz’s second child, Tina, then three, was also invited. In the playgroup, centre staff support parents, and an occupational therapist and speech therapist attend each week to observe and help the children. Staff soon noticed that Tina exhibited some speech delay.

Backed by centre staff, Liz had the children assessed and diagnosed so that they could receive the support they needed. They were both diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and Tina with some speech disorder and other learning disabilities.

Tina was assessed initially in one-on-one sessions at the centre, then in the playgroup and later at kindergarten. This gave her access to occupational therapy and speech pathology support and an early childhood development program for children with disability, an extra day a week for the final year before school. After that year, Tina still wasn’t ready to easily transition to school, so she had another year with the centre to give her the time she needed.

Having received so much support at the centre, Liz wanted to give back so she signed up as a volunteer. Later her employment agency facilitated her taking on casual work, and more recently she has been employed as a permanent, part-time employee assisting with administration and playgroup support.

As Liz says: “I was happy for the help I received at the centre and it benefited my daughter getting ready for school. It was good to have everyone in the one place. Now I get to be a part of helping other people.”

“We want the best outcomes for the children, but you can’t do it in isolation from the parent.”

Cassy Bishop is Manager of the Cairns and Gordonvale Early Years Centres for The Benevolent Society. She said that as a result of the family’s involvement with the centre, the children have been able to get a lot more support at school, and Liz has become stronger emotionally and as a parent through the staff and social supports. “She’s been able to find her way through a relationship break up and the kids are managing at school.

“Getting the diagnosis can open up a whole world of support for them,” said Ms Bishop. “Liz got support for her own intellectual disability for when people are using a lot of jargon or difficult language. Being able to navigate that process with support was a real benefit to her and the children.

“We want the best outcomes for the children, but you can’t do it in isolation from the parent. So your main client is the parent, the family and the extended family.”

Fragmented service delivery and the role of integrated centres

Fragmented service delivery is a common problem across the social service sector. Everyone leads a complex life, and the issues we face don’t necessarily fit into neat boxes. Government services, on the other hand, are delivered in siloes through individual contracts, resulting in multiple individual services with little connection between them.

Services that help with issues such as child and family, early child education, domestic violence, homelessness/housing, health and mental health are all hampered when delivered in a fragmented way. Understanding the impacts of this and how to overcome them is important not only for those working in these systems, but the people designing and funding them as well.

Those with the greatest need are least likely to access the services or receive the comprehensive support they need.

The current early childhood service system in Australia is complex and fragmented. Attempting to navigate this intricate landscape can leave families who are experiencing significant hardship and vulnerability feeling humiliated and disempowered.1

Those with the greatest need are least likely to access the services or receive the comprehensive support they need,2 which undermines the effectiveness and the equity of the system and reduces the value of the money invested.

Social Ventures Australia (SVA) recently launched Happy, healthy and thriving children: Enhancing the impact of Integrated Child and Family Centres in Australia, a discussion paper exploring current ICFC models in Australia. It focuses on the key enablers and barriers impacting the outcomes delivered. Here, we share some of the paper’s findings about the key features of integrated services which ensure families and children get the support they need.

Integrated centres in Australia

Through our research we have defined ICFCs as a service and social hub where children and families can access key early years services and connect with other families. They usually take the form of a centre that provides a range of child and family services – including early learning programs such as playgroups and preschool, maternal and child health and family support programs. Some ICFC models are also community designed and delivered.

ICFCs seek to provide a holistic response to the needs of children and their families and improve the condition under which families are raising young children. An effective integrated centre has the capacity to:

- Identify and support a child’s learning and development needs

- Identify and work with families around broader issues that may be affecting a child’s wellbeing, such as poverty, family violence and marginalisation

- Provide access to early intervention supports

- Provide a safe space for families to socialise and build connections.

Based on the analysis of a variety of centres, we found that a core component of the model is the ‘glue’ – the organisational and staff capabilities that enables coordination and integration of support within and between services. When effectively funded, the ‘glue’ ensures ICFCs are more than co-located services and are able to respond holistically to the needs of children and families.

“The way we work in a multi-disciplinarian model, the staff are all learning from each other… and we all have a little bit of knowledge about what to look out for.”

Ms Bishop from the Cairns and Gordonvale Centres puts this holistic response down to what made such a difference for Liz and her family:

“Having the transdisciplinary team – the child and family practitioners with social work, psychology, early education backgrounds, and the allied health and Queensland health nurses – provided a ‘holistic eye’ on the child. If it was just the social work team, they might not pick up the health, occupational therapist-related stuff. If it was just a health worker, they might not pick up the social issues.

“The way we work in a multi-disciplinarian model, the staff are all learning from each other, not just stuck in our own discipline mindset, and we all have a little bit of knowledge about what to look out for. If we didn’t have that knowledge, at that initial intake, the nurse wouldn’t have picked up that there were other social issues going on, and the senior practitioner wouldn’t have sensed there was some disability or speech-related delays going on. That’s how the integrated space helps the child.”

Current landscape

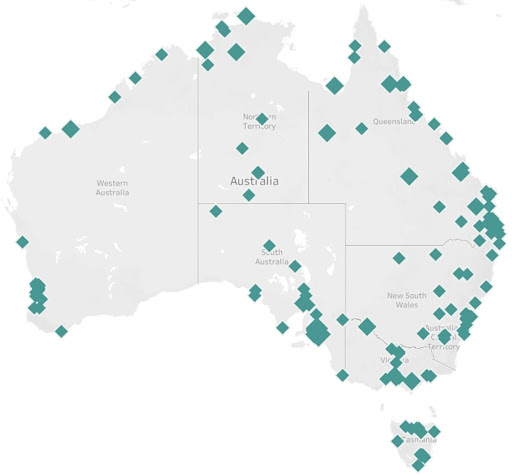

As part of our analysis, we’ve identified that there are approximately 209 centres operating in Australia that meet the definition of an integrated child and family centre set out above. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1. Location of integrated child and family centres.

These comprise six state-run models operating at various levels of scale and capacity, as well as the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander integrated early years centres that operate nationally. There are also other similar models being piloted by philanthropic organisations, including the Our Place approach operating in 10 communities across Victoria.

ICFCs operate under a range of funding mechanisms and operating models. State and territory governments are the main funders of integrated centres. There are ICFCs operating in each jurisdiction, though curiously, the two biggest states – Victoria and NSW – are the only states without a dedicated model in place. Some models, such as the Tasmanian Child and Family Learning Centres, are owned and operated by state governments, while others, such as Queensland’s Early Years Places, are operated by non-government organisations. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander integrated early years centres are the only model operating nationally, with many of these centres operated by Aboriginal community-controlled organisations.

ICFCs are not currently defined nor consistently recognised as a service model in the Australian early years landscape. There is currently no national approach to delivery, and no overall leadership or responsibility for outcomes. And while quality is essential for integrated centre outcomes, there is currently no overarching approach to measuring or assessing quality.

Key findings

Our research included interviews with 20 centre leaders, sector experts and government representatives. We found integrated centres can meet many children and families’ needs when:

- Funding recognises the breadth of their activities

- Centre leaders and workforce are supported and empowered

- Quality is maintained through effective structures and processes

- The operating model enables the structure and practises of the centre.

- Funding recognises the breadth of their activities

Integrated centres need an effective funding model with secure, long-term funding for provision of core services and flexible funding for diverse child and family-related services responsive to community needs. This must include adequate funding for the ‘glue’ – the coordination and integration within and between services.

Many state-funded centres are enabled by adequate ongoing funding that supports their remit as an integrated service. This includes secure, ongoing staffing and operational budgets that fund core operations, the ‘glue’ component, and includes a flexible funding component. Some state-run models, such as the Tasmanian Child and Family Learning Centres, also provide purpose-built infrastructure.

However, state-funded centres are impacted by siloed funding and complex jurisdictional arrangements. This undermines full integration with services funded by other government departments, such as maternal and child health, and also limits state-funded centres from being able to deliver federally funded services such as childcare.

Centres that operate separately to state-funded models notably Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander integrated early years centres describe acute funding challenges that undermine their efforts to deliver an integrated service. These centres are primarily funded through the Child Care Subsidy which is not designed to enable wraparound, holistic services or support services operating in disadvantaged communities. It is intended as a subsidy for working families attending childcare services operating in a competitive market environment.

There is a misalignment between the purpose of the Child Care Subsidy and the core purpose and mission of ICFCs that holistically support the most vulnerable children and families within their community. It also does not support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander integrated early years centres in their mission to support culture, pride and community building for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

- Centre leaders and workforce are supported and empowered

The integrated centre model depends on high-quality leaders who understand their communities and what is required to make an impact. However, structural and funding limitations often limit centre leaders’ ability to implement this vision.

They face significant burdens and often operate with little support or control. Centre leaders and the workforce need to be supported through competitive remuneration, working conditions, practice frameworks and other necessary supports to ensure they can thrive in the role.

The majority of the services provided in integrated centres are predominately government-funded so the ability to invest in building the capability of centre directors is also ultimately a function of how governments choose to fund the services on offer.

Centre leaders also need to be empowered to be innovative and lead the model to ensure it is of a high quality and responsive to family needs. This requires a sophisticated funding and regulatory model to ensure the flexibility to tailor supports and services to the needs of the individual and communities while also ensuring quality assurance and that the services are delivering the outcomes intended.

- Quality is maintained through effective structures and processes

While we have sought to understand the elements that are essential for an effective ICFC, there is currently no mandated or consistent way to assess the quality of the service they provide. Centres have different requirements based on their state location, the types of services that they offer, and how and who they are contracted by.

It is essential that tools are developed to support ICFCs and their broader authorising environments to identify and provide high-quality services and supports. These include quality frameworks at a centre level, as well as a nationally consistent quality framework. It also means we need better data about which indicators represent the best outcomes for children.

- The operating model enables the structures and practices of the centre

The integrated centre operating model needs to enable child-centred practice, an integrated service offering, and a safe space for families to build social networks and access supports. The model needs to incorporate a way of working that is child-focused, relational and multidisciplinary.

The model also needs to be intentionally designed as a space where families with young children can come regardless of whether they are accessing a specific service. The model is also a place where staff members are trained and supported to build relationships with families to make them feel safe, identify their needs and provide appropriate supports.

“… the biggest benefit and most significant change is the social networks that they’ve built.”

As Ms Bishop says: “The centre is a social hub in that the programs that we offer set people up to get those social supports. The centre is a space where parents come. Every day we have a group on, and parents might stay for an hour after the group, or to have lunch with each other, or hang about just chatting to each other.

“Each year we survey more than 100 people who come to our services who say that the biggest benefit and most significant change is the social networks that they’ve built.”

Better integration across state government departments is also needed to support the operating model by enabling integrated funding, overcoming the barriers to data sharing and fully incorporating all services, including maternal and child health services and allied health, into the model.

Currently, the services offered within an ICFC are funded by different parts of the same government (health, education, social services). These services are subject to different funding and reporting requirements and different rules and regulations. This can undermine service integration and make it harder to measure what is and is not working for children and families.

Allied health is a key component of the ICFC operating model and is often embedded into integrated centre programs. Cairns Early Years Centre is an example of this. Although the Queensland Department of Education funds The Benevolent Society to run the Centre, key partnerships exist with Queensland Health, which funds the child health nurses and other allied health practitioners, and the local Aboriginal wellbeing service.

Ms Bishop explains: “The two staff from the Indigenous health service are part of the team and support the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families but they also help build the team’s skills in working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families.”

However, access to therapeutic allied health supports is a systemic gap across integrated centre models. Individual centres and families take on the responsibility for finding, accessing and funding allied health services. There is currently no systemic way to provide these critical services.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander integrated early years centres need a unique response

SNAICC – National Voice for our Children (SNAICC) is the peak body for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, working persistently for over 40 years to bring social justice and policy reform to support the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community-controlled sector, including advocating for a unique funding model that is more responsive to community need.

SNAICC has been instrumental in shaping and reforming the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander early childhood sector through policy and strategy reform work with the federal and state governments and establishing the THRYVE pilot program.

THRYVE provides direct backbone support to see a strong and expanding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community-controlled sector across NSW, Victoria, and Western Australia. The divisions are made up of culturally responsive Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander staff that bring a great sense of passion and experience to the sector.

Integrated service models are not new to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. In fact, they have been relied on by many communities for decades. Cultural safety, strength and inclusion are critical features of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander integrated early years centres.

This model has the most diverse service offering but faces the most significant challenges in terms of its complex operating model which includes numerous funding streams and a lack of support from government funders.

“Cultural safety is paramount. That gives connection to families and community.”

The centres incorporate the three key factors that have emerged from research as being central to improving the access of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in early childhood education and care: local ownership of programs, employment of local people, and incorporation of culture within services.3

Stacey Brown is CEO of Yappera Children’s Service, an Aboriginal community-controlled integrated early years centre in Thornbury, north Melbourne, which has been running for over 40 years. More than 70 per cent of its staff are Aboriginal. Ms Brown says that families accessing Aboriginal early years services deem culture as the priority.

“Cultural safety is paramount. That gives connection to families and community.

“The goals we have for a child leaving Yappera,” says Ms Brown, “is that they are confident, resilient and have a strong sense of identity, so that when going into school, they are proud of who they are, and the families are empowered too.”

SNAICC is making significant strides in building momentum for funding reform and Aboriginal-led approaches to see better supports for these services to fulfil its mission.

How to ensure more children and families benefit from an integrated centre

State and territory governments play a key role in this space. Most have an ICFC model operating at some level of scale across their jurisdiction; they are also actively involved in supporting these centres to achieve outcomes that enable children and families to thrive.

It highlights a critical national leadership role for the Federal Government in providing an umbrella for ICFCs.

However, the level of unmet need across the country requires a significant investment and overarching leadership beyond what any individual state can deliver on its own. It highlights a critical national leadership role for the Federal Government in providing an umbrella for ICFCs to be recognised, defined and supported as a sector, and potentially a greater role in funding and outcome measurement.

A tripartite approach is recommended to bring together the sector and the federal, state and territory governments to develop a collective approach to drive the necessary reforms.

Conclusion

Fragmented service delivery can have a disproportionate impact on people experiencing disadvantage. Integrated centres as exemplified in the early childhood sector demonstrate a way to overcome some of the detrimental impacts of fragmented service delivery and ensure that those children and families who would benefit the most from these services get the support they need.

Our research shows how ICFCs can increase their impact on outcomes for children and their families. It also assists in framing a national approach to ICFCs and identifying critical systemic reforms that could see significantly more children in Australia thriving in the early years.

For more information, contact Caitlin Graham on [email protected]

About the author:

Caitlin Graham is a dedicated social justice advocate with over a decade of experience in developing impactful social policy for various not-for-profits, local and state governments. With a strong background in research, policy development, advocacy and systems change, Caitlin has demonstrated expertise across a broad range of policy areas including early childhood, youth, and international corruption.

Caitlin is driven by her passion to ensure that all children have the opportunity to thrive, regardless of where they live or the challenges their families may face. Her commitment to this vision aligns seamlessly with the Young Children Thriving (YCT) Program led by Social Ventures Australia (SVA), which aims to transform the early childhood development landscape and provide proactive and responsive supports to children experiencing vulnerability when they need it most.

This article was first published in the SVA Quarterly by Social Ventures Australia.

Notes

1 McLoughlin, S Newman and F McKenzie, Why Our Place? Evidence behind the approach, Our Place, 2020.

2 S Fox, A Southwell, N Stafford, R Goodhue, D Jackson and C Smith, Better systems, better chances: a review of research and practice for prevention and early intervention, Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth (ARACY), 2015.

3 E Sydenham, Ensuring equality for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in the early years [PDF] [discussion paper], Early Childhood Australia (ECA) and SNAICC – National Voice for our Children, 2019.

Popular

Quality

Practice

Provider

Research

Workforce

Honouring the quiet magic of early childhood

2025-07-11 09:15:00

by Fiona Alston

Practice

Provider

Quality

Research

Workforce

New activity booklet supports everyday conversations to keep children safe

2025-07-10 09:00:16

by Fiona Alston

Quality

Practice

Provider

Workforce

Reclaiming Joy: Why connection, curiosity and care still matter in early childhood education

2025-07-09 10:00:07

by Fiona Alston