New international study into severe speech disorder, apraxia

A team of Melbourne researchers have led an international study that has discovered nine new genes linked to the most severe type of childhood speech disorder, apraxia.

One in every thousand children has apraxia, and despite intensive investigation the genetic origins of this debilitating speech disorder have remained largely unexplained, until now, making the findings significant on a global scale.

Apraxia is the most severe form of childhood speech disorder. When a child experiences apraxia of speech, the messages which go from the brain to the mouth are not delivered correctly.

As a result, the child might not be able to move their lips or tongue in the right ways, even though their muscles are strong. Sometimes children may not be able to communicate effectively as a result.

Children living with apraxia, which is sometimes known as verbal dyspraxia or developmental apraxia are not able to “outgrow” the issue, will not learn speech sounds in a typical order, and will likely require treatment in order to be understood.

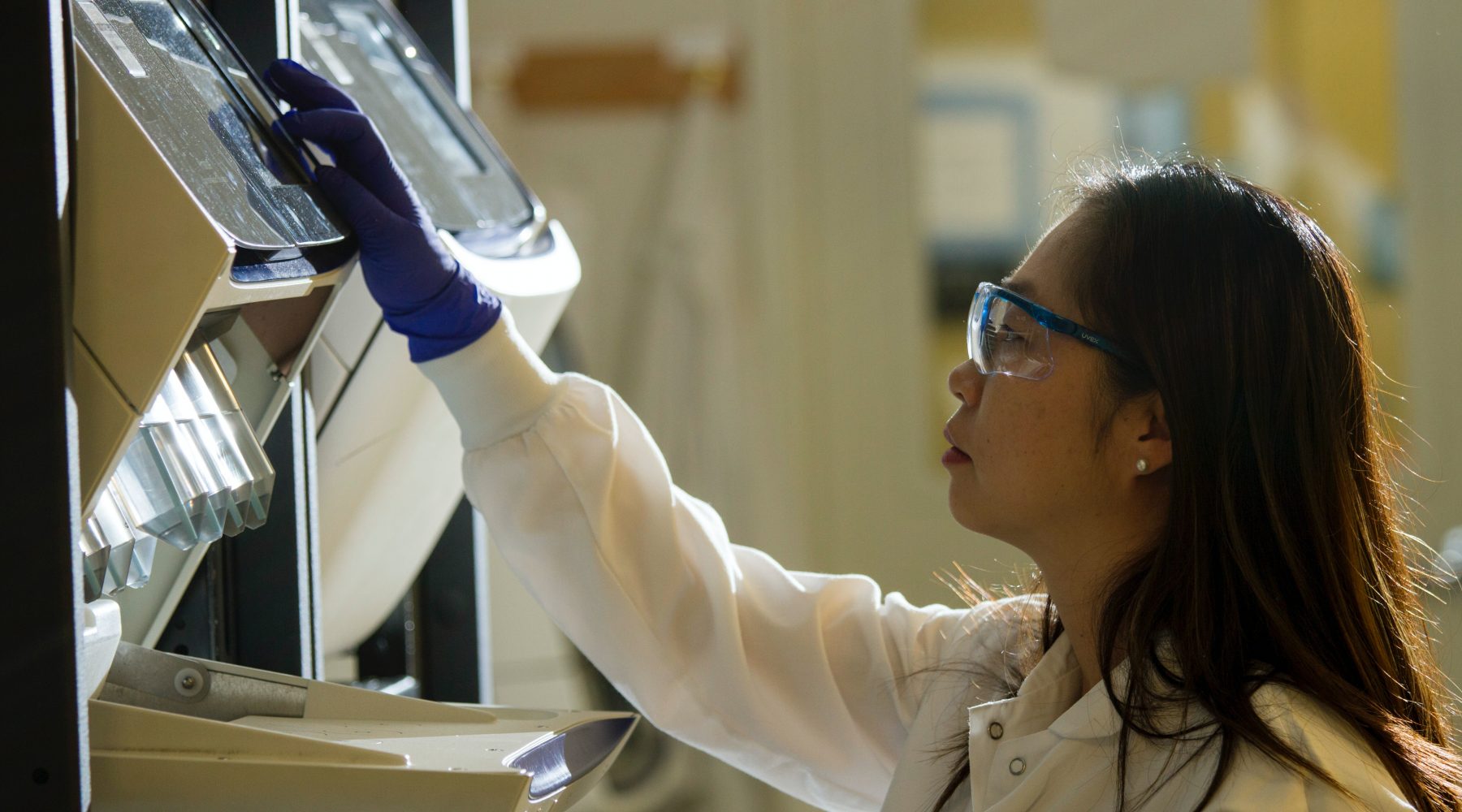

The recent study analysed the genetic make-up of 34 affected children and young people, and showed that variations in nine genes likely explained apraxia in 11 of them. The genetic variations were caused spontaneously and not inherited from their parents.

University of Melbourne Professor of Speech Pathology Angela Morgan explained that “eight of the nine genes are critical in a process which turns specific language genes “on” or “off” by binding to nearby DNA.”

“We found these eight genes are activated in the developing brain. This suggests there is at least one genetic network for apraxia, all with a similar function and expression pattern in the brain,” she added.

Professor Morgan said the new genetic findings would help neuroscientists and speech pathologists develop more targeted treatments for children, noting the “socially debilitating” nature of apraxia.

“Children with apraxia typically have problems developing speech from infancy, with a history of poor feeding, limited babbling, delayed onset of first words, and highly unintelligible speech into the preschool years. Diagnosis is usually made when they are around age three,” Professor Morgan said.

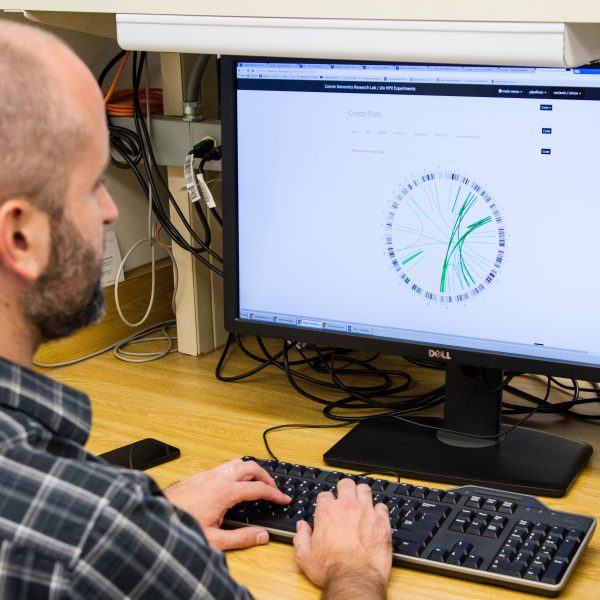

The research, led by the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute (MCRI), the University of Melbourne and the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, was recently published in the online issue of Neurology®, the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology.

To learn more about the University’s work in the field of apraxia, please see here.

Popular

Policy

Practice

Provider

Quality

Research

Workforce

Beyond the headlines: celebrating educators and the power of positive relationships in early learning

2025-07-07 10:00:24

by Fiona Alston

Workforce

Policy

Quality

Practice

Provider

Research

ECEC must change now, our children can’t wait for another inquiry

2025-07-02 07:47:14

by Fiona Alston

Workforce

Quality

Practice

Provider

Research

Beyond the finish line: Championing child protection one marathon at a time

2025-07-08 09:15:32

by Fiona Alston