Want young children to choose healthier options? Not what you say, but how, study finds

Young children tend to respond to questions of choice with the option they heard last, so if you want them to choose broccoli and not cake, make sure you present broccoli as the second option, researchers have learnt.

Lead author Emily Sumner, a doctoral candidate at the University of California, Irvine, said that one of the greatest challenges for parents and developmental psychologists alike is figuring out what children are thinking, something which is particularly difficult to determine in early childhood.

“Our findings suggest that some youngsters’ verbal responses may be the result of recency bias – repeating what they last heard – and don’t necessarily indicate that they comprehend the words they speak,” she said.

Recently published in the online journal PLOS One, researchers found that toddlers are highly subject to “recency bias” when faced with “or” questions: They tend to pick the last option, even if it’s not what they actually want.

“Adults are able to distinguish between choices and are oftentimes more likely to select the first one. This is called primacy bias,” Ms Sumner said.

“Children, however, and particularly toddlers under three, who may not know language as well, demonstrate a recency bias when responding to questions verbally, meaning the last choice presented is more often selected. This area hasn’t been studied in children before, so this is fascinating to pinpoint.”

Researchers asked 24 toddlers between 21 and 27 months old 20 questions in which they had to choose between option one and option two. They then posed the same questions again, with the options in reverse order. After speaking each answer, the children were given a sticker depicting their selection. If they didn’t say which option they wanted, both stickers were shown when the question was asked, and they pointed to their choice.

When toddlers responded verbally, they picked the last option presented 85.2 per cent of the time. When pointing rather than speaking, they chose the last option only 51.6 per cent of the time. According to Ms Sumner, this difference is related to the development of children’s working memory, which is concerned with immediate conscious perception and linguistic processing, along with something called the phonological loop.

When the child had the option to point at a response, they could see the options, and then choose their actual preference, but when they had no visual references, and only hear the “or” option, they are able to then “latch on” to the most recently mentioned option by relying on the phonological loop.

“The children understand how speech sounds but not necessarily what the words mean. So when speaking, they’re just parroting back the most recently mentioned choice.” Ms Sumner explained.

The researchers also reviewed the Child Language Data Exchange System, a computerised database of transcribed conversations between parents and their children to determine if the same bias applies in real-world interactions.

They analysed 534 “or” questions and discovered that the likelihood of responding with the second option decreased as children got older. It was selected 64 per cent of the time by two-year-olds, while three- and four-year-olds chose the second option 50 per cent of the time. This suggests that recency bias is present until about the age of three.

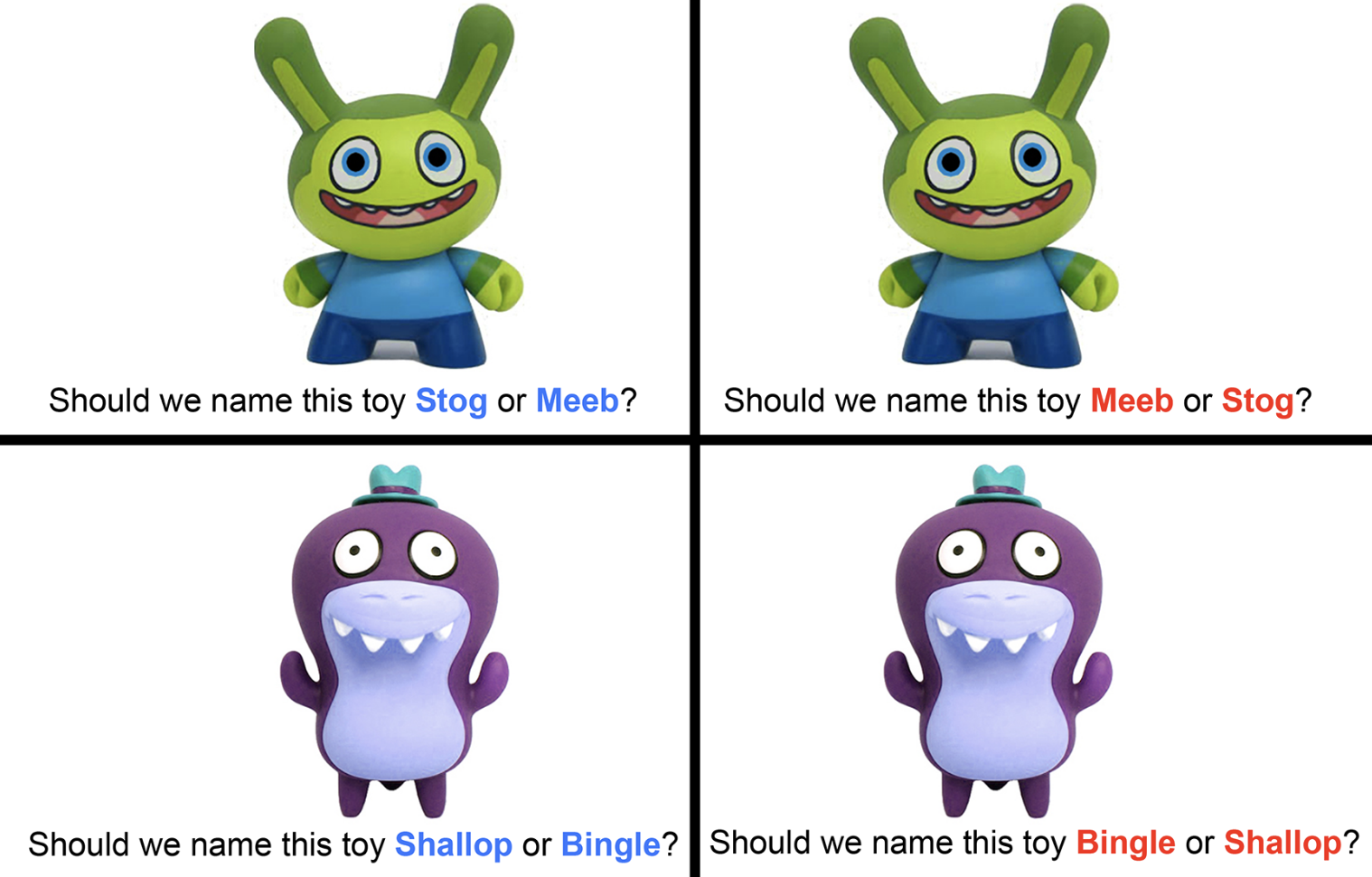

Additional experiments were conducted with 24 preschoolers to determine if working memory constraints, such as age and word length, drive recency bias. The children were asked to name toy cartoon characters by choosing between two nonsense words varying in syllable count – Stog or Meeb, for example, or Hootamawhirl or Haykidosi.

Researchers found that most preschoolers were apt to exhibit a recency bias throughout the entire process. Further results showed that with most of the children, the more syllables the words had, the stronger the recency bias. This suggests that when working memory is constrained, even older kids are more likely to revert back to recency bias.

“Our study demonstrates the importance of swapping the order of options when asking young children about their preferences, because they don’t always know what they’re saying,” Ms Sumner said. “For experimental psychologists, research methods that require verbal responses should be carefully counterbalanced. Parents, however, may wish to use such a biased design when asking toddlers if they’d like cake or broccoli.”

Researchers involved in the project came from the University of Minnesota; University of Rochester; Stanford University; University of California, Berkeley. The study was funded by the Jacobs Foundation and the University of Rochester Bilski-Mayer fellowship program, and may be accessed here.

Popular

Policy

Practice

Provider

Quality

NSW Government launches sweeping reforms to improve safety and transparency in early learning

2025-06-30 10:02:40

by Fiona Alston

Quality

Provider

Policy

Practice

WA approved provider fined $45,000 over bush excursion incident

2025-07-01 07:00:01

by Fiona Alston

Workforce

Policy

Quality

Practice

Provider

Research

ECEC must change now, our children can’t wait for another inquiry

2025-07-02 07:47:14

by Fiona Alston