What is a futurist, and why should ECEC care?

opinion

The views expressed by contributors are their own and not the view of The Sector.

What did you want to be when you grew up? I wanted to be a paediatrician. I loved babies. I loved helping people, and I loved the idea that I could spend the day with babies, and help them to get better.

Some really negative experiences with hospitals soon turned me off that idea, and instead, I was drawn to early education and care. I still love babies, and helping people, and I don’t have to worry about the sad parts which must come to paediatricians when they can’t make children better.

At no point in my career planning as a young child did I consider the skills I would need to become a paediatrician, nor if my early and middle childhood learning would prepare me for the role I wanted.

It’s just as well I didn’t, because the world in 1996, when I finished high school, and in 2001, when I graduated university, looked vastly different from 1981, when I imagined I would be a baby doctor.

The way I search for information, process information, and share my work is vastly different from anything I prepared for in preschool, primary school, and even, to an extent, high school and university.

Enter the futurists

Many of those working in the early childhood education and care (ECEC) sector firmly believe in the potential of children. As a collective, we believe the children are our future, and it’s our job to teach them well, and let them lead the way – but how can we lead the way to a future we can’t see?

It’s the job of a futurist to imagine that which we cannot yet see, and to help various professions predict what they might need along the way, in order to produce the best outcomes and optimal experiences for those they serve.

In essence, a futurist is one who makes highly educated estimates about the future.

The notion of a futurist, and their role in education and care, is not a new one. In 1975, one such futurist suggested that “the curriculum for tomorrow’s educational programs must help young learners recognise that the future is literally created by their decisions”.

In 1981, one futurist called (somewhat coarsely) for an approach to education that balanced cognitive skills and social and emotional learning, cautioning that failing to get the balance right doomed society to “smart psychotics, or well adjusted dopes”.

Thankfully, his calls were balanced by an academic peer in 1980, who suggested future educational directions that focused on “not merely those human qualities considered useful by the industrial and commercial interests of society, but on the entire range of human capacities, so that each person becomes aware of (his or her) self entirely – mind, body, feelings, spirit, imagination”.

With one of the core practices of the Early Years Learning Framework being holistic approaches to teaching and learning, recognising the connectedness of mind, body and spirit, on this, we can say the futurists of the 1970s and 1980s were heeded – but what of the futurists of today?

Predicting tomorrow

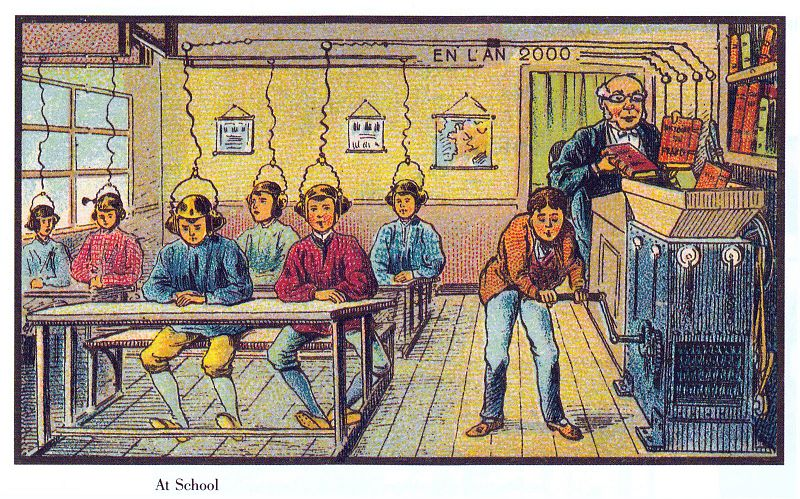

There’s a variety of perspectives about what education might look like in the future. Peter Hutton, from the Future Schools Alliance used the image below to illustrate the 19th Century imagining of what education would look like today.

What elements of our current education and care system are shown in this picture?

Mr Hutton believes one of the core components of education in the future is something we already see today – an increased reliance on technology, artificial intelligence, machine-based intelligence, and devices which are able to understand emotion – something Mr Hutton believes is coming within the next five years.

Of particular importance for those working in early childhood settings, in terms of predicting tomorrow, is the concept of a digital twin – a record of preferences, with the capacity to read microexpressions.

Currently, a digital twin is a computer program that takes real world data about a physical object or system as inputs, and produces as outputs predictions or simulations of how that physical object or system will be affected by those inputs.

As the technology presently stands, a digital twin of a building can be subjected to models of wind and rainstorms, earthquakes and tidal waves, to see how it will withstand impact – all before being built.

In the future, digital twin technology could become so embedded into our technological tools that it is able to support humans in their daily lives, and optimise their experiences.

For example, instead of entering a coffee shop and placing an order, the technology behind the digital twin knows your preferred order, based on past preferences. As you drink your coffee, the technology monitors your face, recording your microexpressions, noting that perhaps the coffee today was too bitter, adjusting it for tomorrow, and learning ever more about your preferences.

Digital twin technology is already in place in many education and care settings – consider the two year old who walks up to a digital assistant and says “Google! Baby shark!” The child’s preference for baby shark, often multiple times, helps the assistant to learn the child’s needs. The same child, walking up to the assistant and saying “Google! Play song!” is more likely to hear baby shark than Deep Purple’s ‘Smoke on the water’.

According to Mr Hutton, children growing up today will likely have a digital twin that helps them to avoid people they don’t like, find those that they do, sets them up for a comforting nights sleep, reach out to their teachers when they need assistance, and build resilience through carefully managed challenges designed to test and develop skills.

For educators, the presence of a digital twin in the life of a child will mean more data – more knowledge about the sort of sleep a child had the night before, who might need more emotional support on any given day, insight into a child’s mood, and so much more.

What next?

There’s no way of knowing, of course, exactly what will happen next, and when. The only thing that stays the same is change, which is inevitable. So how do educators prepare children to participate and function in a world they can’t yet see?

According to Mr Hutton, it’s about giving children generalist skills. It’s not about preparing for a situation we don’t yet know, but it’s about anticipating that change will happen, shaping children to become change positive or change neutral.

It’s also, he said, about looking up and around.

When I was small, I learnt about how to be a mother from watching my own mother, and the mothers around me. I learn now about a wide range of topics from looking up and looking around – at those professionals I admire, watching TED Talks, reading widely, and seeking opportunities for learning. Looking up and looking around gives great guidance about what’s happening next.

To know more about what is likely to happen in the world of ECEC, we may look up to what’s happening in the world of schools. We may look around to sites and systems of innovation in other parts of the world. We may also look to adjacent sectors, such as community service organisations, or health care, for guidance and perspective about trends and directions.

Many ECEC sectors are incorporating advanced technologies to optimise the experience of children in their care. The Sector recently wrote about Dubai’s Ora Nursery, which uses customised sleep pods with temperature and movement monitoring sensors that will help to create sleeping environments that are safe, effective and data heavy, ready to feed information back to parents and carers about a child’s movements, temperature and breathing patterns as they sleep.

The strongest piece of advice Mr Hutton had for other educators looking to succeed in the innovation space was to connect up with others who are interested in looking forward.

Mr Hutton’s presentation on educational futurism can be viewed here.

Other resources about futurists and future outcomes may be viewed in the links above.

Popular

Practice

Provider

Quality

Research

Workforce

New activity booklet supports everyday conversations to keep children safe

2025-07-10 09:00:16

by Fiona Alston

Quality

Practice

Provider

Research

Workforce

Honouring the quiet magic of early childhood

2025-07-11 09:15:00

by Fiona Alston

Quality

Practice

Provider

Workforce

Reclaiming Joy: Why connection, curiosity and care still matter in early childhood education

2025-07-09 10:00:07

by Fiona Alston