The Big Storm: a reflection on children’s voices in educator documentation

opinion

The views expressed by contributors are their own and not the view of The Sector.

ACECQA has shared data over an extended period of time, showing that documenting children’s learning, in particular demonstrating the cycle of planning, is a challenge for the early childhood education and care (ECEC) sector. In this piece, early childhood educator Samantha (Sam) Newberry explores the importance of including children’s voices, providing practical examples of questions, provocations and perspectives all educators can use in their daily work with children.

Have you ever noticed that almost all of the ‘wow moments’, where we really gain insight and understanding of children’s knowledge of their world, happen when we may not expect it – and almost always when a pen and paper is not handy?

Educators need to be flexible and think on our feet, but sometimes we can feel ‘stuck’ in the way we collect information and document children’s ideas, thoughts and learning.

It is easy to get bogged down in what happened, and what we think children might be learning, analysing and thinking through how we can extend on learning through intentional teaching and experiences, writing long-winded narratives that are time consuming. I wonder if parents read these? I wonder how much time we spend trying to get that photo or convincing a child to let us glue that piece of art they worked so hard on, into a book.

If we focused more on recording and valuing what children say and think, would we see an increase or decrease in the amount of documentation ‘work’ that needed to be done? Is it possible to show a clear cycle of planning and a continuum of learning through simply recording children’s ideas and valuing the knowledge at this point of time? If we were to capture children’s voices during play as they occur naturally and without too much adult intervention, would this serve as an accurate enough assessment of learning?

As educators, we plan intentional experiences, we program, we aim to use our resources and knowledge to inspire learning in children. We spend countless hours trying to document so that parents, educators and assessors are able to see the learning, and yet for me, the most valuable gauge of my teaching was standing under the veranda with a group of children watching the thunderstorm roll across the yard. Witnessing the torrential rain, the sound of the wind, the clap of thunder and the stark flash of the lightning, the depth of the children’s learning, and my skill as an educator, became instantly visible.

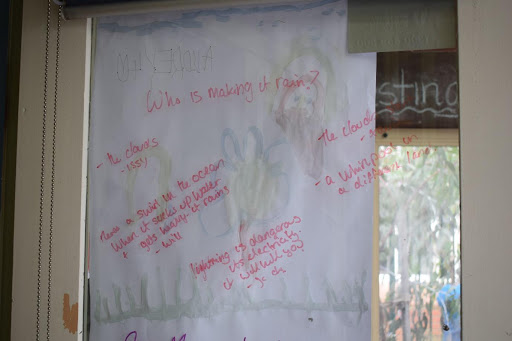

Who’s making it rain?

“Who’s making it rain?” asked one child.

Who indeed?

“What do you think? What do we know about the rain?” I pondered aloud.

“It rains when there’s a whirlpool that goes across the ocean and sucks it up into the clouds and makes the clouds heavy and the water falls out.”

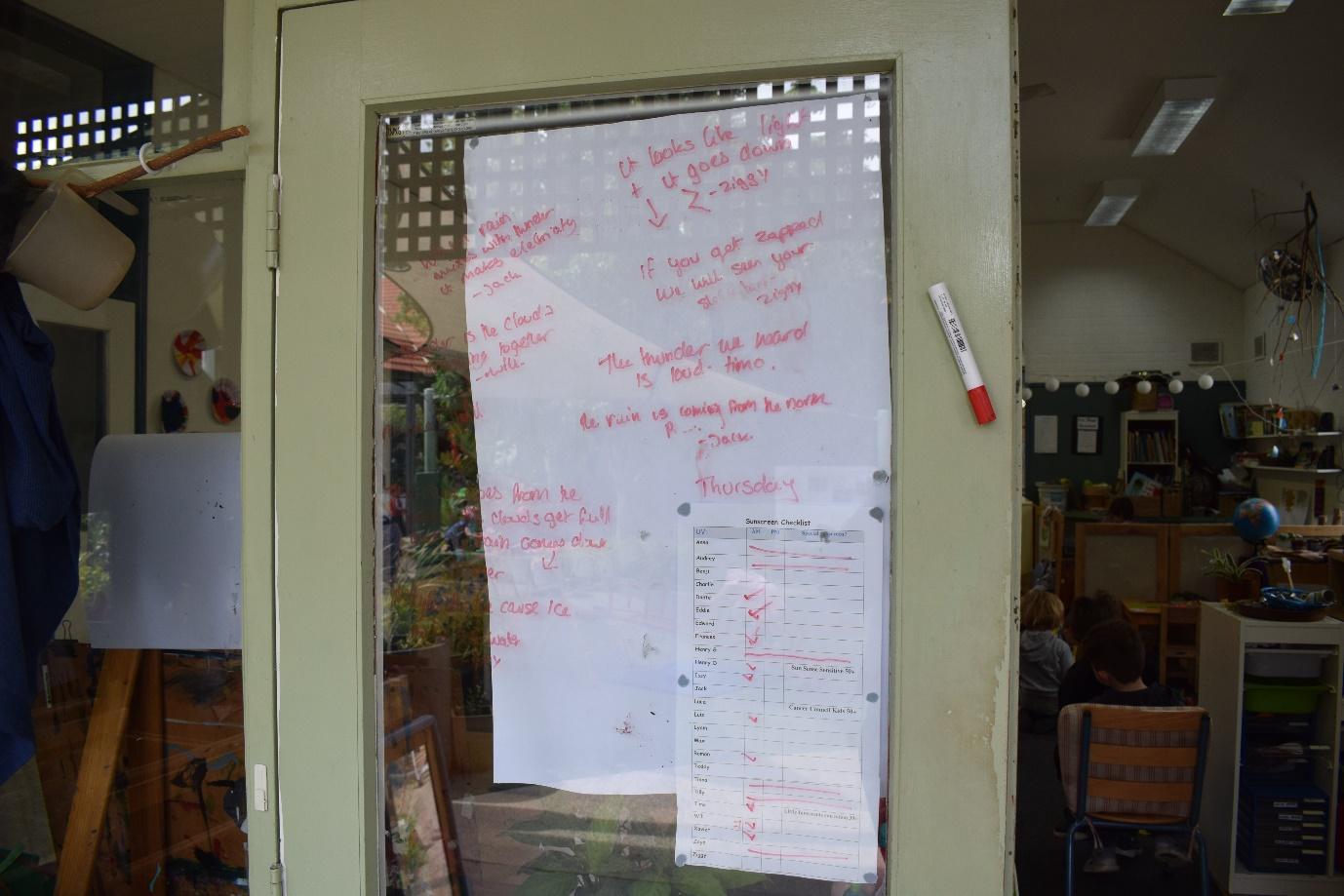

Babbles of voices, competing over the sound of the rain. So much learning and scientific thinking going on. Hypothesising and critically reflecting on each other’s theories and knowledge. Sharing their observations with me and their peers. I needed to record this, but couldn’t step away to go and get a camera, an iPad, or even a pen and paper. I did however, have a whiteboard marker that was used for marking off our sun cream list.

I wrote up the starting question, straight onto the window. “who is making it rain?” and then stepped back and allowed the children to voice their theory and have it recorded, straight onto the glass. I did not try to explain the science behind rain, the water cycle, the sound of the lightning – that wasn’t the important part. The important part was recording, and giving immediate and visual merit and validation to their ideas.

Their ideas changed and grew as they listened to their peers. They wildly changed focus, and sometimes I wondered at their jump. As each new child walked out into our veranda, I posed the original question to them, and watched in amazement as they joined the swirling mess of scientific theories.

“Look at the huge puddle! It’s so big! It’s the biggest ever!”

“No one is making it rain!”

“Yes, the rain comes from the clouds, maybe in the clouds there is ice and the ice melted and that’s why it’s raining.”

“The rain is coming from the north.”

How much rain do you think there is? How could we measure that?

“Count the rain drops!”…”Catch it in a big puddle”…. “Put the rain in a bucket and use a measurer!”

I volunteered to fetch the upturned bucket and place it so it could catch the rain, the children squealed and laughed at my wet body and experimented with their fingers into the rain. They marvelled at the water appearing in the bucket, but more interesting was the steady gushing of the storm water pipe onto the outdoor bench.

“The thunder is the clouds booming together”

“The thunder is so loud! CRASH!”

”When you get zapped with lightening you can see your skeleton cause its electricity” (a stark example of how media plays a role in a child’s understanding of the world around them.)

“It looks like light, and it goes *the child draws a sharp, zig zag through the air starting from his head and flowing downwards*”

Writing on the glass, as these comments flew out at me, I marvelled at this display of knowledge and skill. Of scientific concepts, practical knowledge and wild flights of fantasy.

I don’t need to write about the learning, because the learning is visible already. Sure, the ‘facts’ aren’t there, it’s not ‘correct’ science. But these children have shown exactly what they know, why they know it, and feel confident to share in this exchange of learning. This is the value of learning within a group, in having a connection with others we are able to co-construct knowledge, build on our theories of the universe – and perhaps most importantly be challenged, and learn how to respond to challenges.

When we record the voice of the child, we are acknowledging their individual knowledge and perspectives at this point in time. This direct knowledge allows educators to gain insight into the child’s thinking and development, and deeply consider how to intentionally engage with this child’s learning.

Feeling confident enough to record children’s ideas in a variety of ways (a voice recording, a sticky note, a scrap of paper, writing on the window) gives educators the chance to reflect on their practice, and the children they educate. When children see, and hear us giving their words importance and meaning, they are empowered to share their thinking and knowledge with even greater freedom.

The storm passes, the learning stays

The rain slowed, and stopped. The children left, and I took photos of the writing on the windows. It’s not pretty, and it’s kind of hard to read, but it’s there. I am going to revisit the spark question again and I’ll try and record the thinking, see if it has grown and changed, if they recall the same knowledge and hypothesis without the catalyst of the storm. Maybe they will, maybe they won’t but I know it’s there, and that is enough.

In exploring this learning, and the involvement of children in documenting their learning journey, the following reflective questions may be useful to educators:

- How easy is it to record children’s ideas and knowledge within our documentation?

- Is it authentic and worthwhile documentation if children’s knowledge and opinions on the learning is not included?

- When we add photos, we capture the image of a child, we capture what they are doing, and perhaps their expression. Is this enough for authentic, genuinely useful and interesting documentation of learning?

- Is simply recording the words and ideas of the children we teach enough to satisfy the planning and documentation that we need to display?

It’s sometimes overwhelming in the kinder room when we try and collect children’s voices, sometimes it feels like there are too many words to actually collect! Too much going on, too many ideas and theories and, not all of it is relevant, useful or insightful.

Just as adults, perhaps even more so, children’s words are not always serious, thoughtful, insightful or relevant to the knowledge or ideas we are trying to investigate.

Adults spend time talking, joking, laughing and making up stories when we are in the presence of familiar and trusted people. Sure, sometimes we spend time connecting meaningfully with others, or sharing moments of understanding and clarity – but how often? Not all of children’s words are useful when documenting learning, but the ability to converse, share and probe deeper into children’s knowledge is an invaluable tool.

What’s important – the rain, or who made it?

When recording children’s learning, it is good to consider who determines what is ‘important’.

A child who answers ‘magic’ to the question of how a plane flies is still focused on explaining their theory and is drawing from their contextual knowledge and current understanding of the world around them. The simple (and maybe incorrect) answer is still an invaluable moment to acknowledge and document, if only to be looked back on and marvel at how the child changed their ideas, or if they didn’t why they think the same one is still correct.

Questions to guide critical reflection in the space where educators are determining what is ‘important’ enough to be recorded include:

- What was it that prompted this child to build on their previous answer?

- Were they able to change their ideas, on receiving new knowledge, or is it a core belief that may take time and energy to change?

- Do we need to change a child’s mind, or are we there simply to provide a platform for children to give and receive knowledge and ideas and take from them as they will?

As educators, we have a unique responsibility to engage with what a child is thinking and learning. We have the power to impact thoughts and learning with our presence and our words. When we stop, and actually listen to children and give their words power and meaning we empower children to be voices of change.

Early childhood educator, Samantha (Sam) Newbury works for a centre in South Melbourne, with a strong focus on encouraging educators to engage in in-depth critical reflection on practice and personal pedagogy. This piece of writing forms part of Sam’s reflective practice journey.

Popular

Policy

Practice

Provider

Quality

NSW Government launches sweeping reforms to improve safety and transparency in early learning

2025-06-30 10:02:40

by Fiona Alston

Quality

Provider

Policy

Practice

WA approved provider fined $45,000 over bush excursion incident

2025-07-01 07:00:01

by Fiona Alston

Workforce

Policy

Quality

Practice

Provider

Research

ECEC must change now, our children can’t wait for another inquiry

2025-07-02 07:47:14

by Fiona Alston