The Village – a valuable resource for educators to walk children through cancer journey

Katrina Lau Hammond has an important, difficult and complex story to share which came about from a deeply personal journey navigating breast cancer.

When she was first diagnosed, her eldest child, now a seven year old, was just three years of age. She searched for resources to help her explain the cancer journey she was on in an age appropriate yet accurate way, and came up blank.

She then decided to use her experience to create a children’s book, The Village, which helps explain cancer to children while also raising money for cancer research. Her story has recently been published, and The Sector spoke with Ms Lau Hammond to learn more about her work, the need to support children and families in this space, and how educators can best assist children who find themselves navigating the world of cancer with someone close to them.

The Village

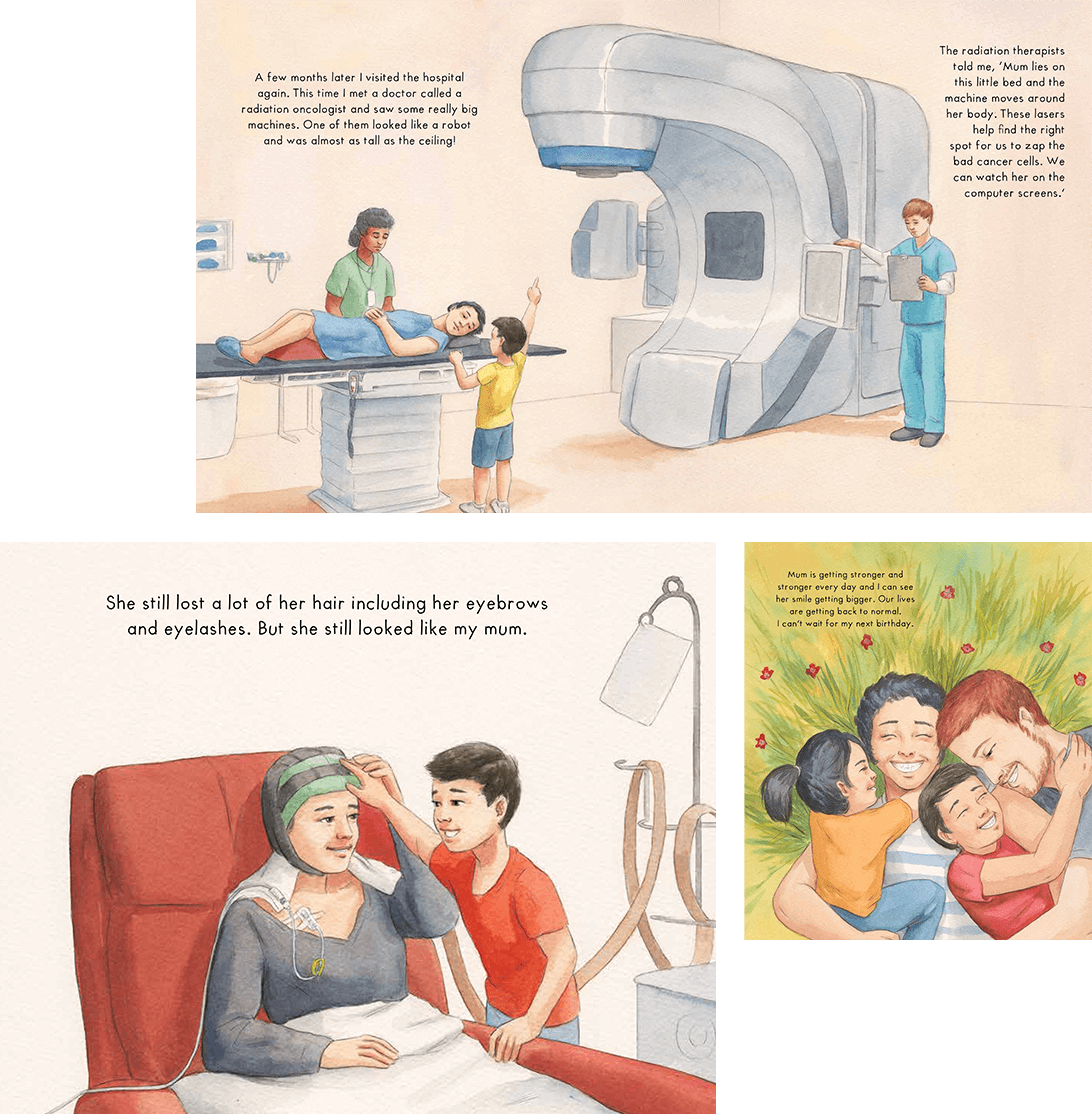

The Village tells a cancer story from the perspective of the child who talks about the diagnosis of someone close to him and how it affects him and his family. It describes contemporary cancer treatments and therapies and introduces children to the specialists who help care for cancer patients.

“I’ve written the book with the intention of being applied across many different types of cancers, not just breast cancer like I had, and tried to show a broad representation across patients and health care workers,” Ms Lau Hammond said.

The story is suitable for children as young as three years of age, but could be read by children as old as 12 years of age, and aims to empower young children with language that is relevant to their family at that time, with proper medical terms, likely the same ones they’d be overhearing every day, with a more detailed glossary at the back for those who seek further explanation.

The book was produced with crowdfunding from preschool and school communities, friends and family. It took Ms Lau Hammond three years to write, interrupted by various cancer treatments following three diagnoses.

“Nobody ever wants to have that conversation with their kids, to tell them that they have a life-threatening illness. But kids are intelligent, perceptive, inquisitive human beings,” she said.

“They’ll pick up on your little cues and the change in mood, even if you are trying not to tell them. I believe that if you continue to hide things from them, they create their own little stories in their head, and that can often be far scarier than the reality.”

Common missteps educators make when working with families living with cancer

We began our conversation by asking about some of the common missteps that educators make when working with children and families on a journey with cancer, and how might these be avoided.

“Talking about cancer, or death, can be a really challenging and intimidating conversation for adults and children,” Ms Lau Hammond said, “so it is only natural to want to avoid discussing these topics. Understandably, adults may prefer to protect children from traumatic experiences and not want to burden them with the harsh reality of a serious illness.”

Despite these challenges, the way that caring adults, including educators, talk to children about cancer is changing, she believes.

Some families may want to be open and honest with their children about their diagnosis, treatment, side effects and recovery. Other families may choose to remain private and not share any details with their children, preferring that no one know about their illness. These preferences may change over time, so open lines of communication between educators, children and families should be maintained.

Is cancer just too sad/hard/difficult/complex for children to understand?

“Cancer certainly is all those things, but young children continue to demonstrate just how much they can absorb, analyse and understand,” Ms Lau Hammond said.

“Previously, many factors may have stopped an adult from talking openly about cancer – fear, shame, stigma, taboo, too difficult, too painful. I think we need to model for our children that adults too can feel sad, distressed, confused, unsure, afraid, but that the feelings change and we work our way through them.”

Some adults may think that cancer is too scary for kids, too tricky or “not for children’s ears”, and prefer not to tell them about it. But children (including babies) are so perceptive to change and their parents’ emotional states, that it would be impossible to hide something as big as cancer from them, she continued.

“From a young age, children are hardwired to detect changes in their parents for survival, so they are often very aware that something is going on in the family even if they are not told explicitly. If they have questions or concerns but are told not to ask or worry, they may bottle up those fears and anxieties, or sit alone with their feelings and misinformation. They might learn not to talk about it, making it hard for anyone to explain things and guide or support them.”

This bottling up and shutting down may leave gaps in children’s knowledge, leaving them to make up their own story about what is happening, what their parent is doing at hospital, whether they will come back or not, and feel alone in their worry.

“Children benefit from access to age-appropriate honest information. Their fear of the unknown can be supported by allowing them to ask questions, providing honest answers and sharing age-appropriate information in a format they can relate to, for example via picture books.”

Having open, honest, age-appropriate conversations with children about what’s happening gives them permission to talk about their worries and fears, so that caring adults can support them through big emotions, help them process their thoughts, and correct any misinformation.

“Nobody wants to tell their kids they have cancer, but sometimes you have to. If the family is being thrust into it, why not arm the children with the right tools?” Ms Lau Hammond said.

Practical ways that educators and services can support

Making sure that the education and care setting is a safe place, where children know they can talk to their educators if they are worried or upset is the most important way services can be of support.

Part of making a safe space involves good communication amongst the team, where staff members talking to one another helps to alleviate having to have the same difficult conversation or complex explanation over and over.

Other simple tips include:

- Remember that parents do not always know the answer to open-ended questions like “what can we do to help?” and that sometimes it can be more helpful to simply offer to cook a meal, provide additional care, or support the family in some other way.

- Research resources, like The Village, and use these to help the child, and other children in the community to understand the experiences of families living with cancer

- Be ready to direct families to resources such as counselling services, community organisations, as well as sourcing resources and support from organisations such as Camp Quality, CanTeen, The Cancer Council and Kids Helpline.

- Check in regularly with the child and their family, and remain present and open to any big feelings which are shared.

- Offer to be a coordination point for offers of help from the broader community, such as meals, play dates, to drop off and pick up children and fundraising efforts.

To order a copy of The Village, or for more information, please see here.

Popular

Workforce

Policy

Quality

Practice

Provider

Research

ECEC must change now, our children can’t wait for another inquiry

2025-07-02 07:47:14

by Fiona Alston

Events News

Workforce

Marketplace

Practice

Quality

Provider

Research

An exclusive “Fireside Chat” with ECEC Champion Myra Geddes

2025-07-01 11:25:05

by Fiona Alston

Workforce

Practice

Provider

Quality

Research

Supporting successful transitions: Big moves, big feelings

2025-06-26 11:00:30

by Fiona Alston