Building Momentum: Positioning Child Mental Health for Policy and Practice Change

The National Children’s Mental Health and Wellbeing Strategy will soon be released in Australia. Recent attention given to children’s mental health in the media and policy and practice circles suggests it will be met by an audience eager to respond to its priorities.

Despite the complexity of the issue, child mental health is on the radar as an important social policy issue and there is a growing appetite for systemic reform.

However, this wasn’t always the case. Ten to fifteen years ago, most people, even members of the early childhood sector, would have questioned the wisdom of devoting limited early childhood resources to building and supporting mental health in young children.

Despite this, and as a result of smart, disciplined, and careful work by a group of organisations focused on advancing the issue, understandings of the importance of child mental health have come a long way.

For example, the Mental Health in Primary Schools (MHiPS) project is testing the power of using a common language to improve mental health and wellbeing; the Raising Children Network’s A-Z index of evidence-based content is supporting parents through clear communication on child mental health; and Be You is working with early learning educators across the country to develop positive, inclusive, and resilient learning communities that support mental health.

For the momentum to continue, advocates and researchers need to keep pushing for better understanding of what child mental health is, why it matters, and what needs to be done to support it in all of Australia’s children. This means continuing to build understanding among the early childhood sector and policy makers, but also in the public domain.

In order to fully support children’s mental health, there needs to not only be a willingness to make change at the top but public demand for it from the bottom up. This will be vital for ensuring that the uptick of interest we are seeing is not just a fleeting ‘flavor of the month.’

Maintaining this momentum will not be easy; cultural mindsets about children, mental health, parenting, science, and society can get in the way.

For example, we have found that people have a tendency to hear messages about mental health as being about mental health problems. This impedes people’s ability to see the importance of supporting positive mental health in proactive and preventative ways.

There is also an implicit understanding in Australia that very young children don’t yet have significant mental states and therefore don’t have mental health. This complicates the ability to advocate for the need for programs to support early child mental health: if young kids don’t have it, why would we invest limited resources in addressing it?

Pervasive mindsets about mental health being an issue of individual choice and control also heavily impact this space.

When viewed in this way, problems with mental health are remediated by deciding to exert control over your mental state and positive mental health is a function of choosing to have the right attitude. This mindset undermines support for programs designed to provide external supports for what people see as an internal phenomenon under individual control.

Finally, we have found a strongly deterministic understanding of children’s mental health—that once a problem has been observed, a child is destined to struggle and be unwell for life. This understanding depresses support for child mental health programs as it makes such efforts seem futile and fruitless.

These cultural mindsets make it hard for people to grasp the concept of child mental health and to get behind calls to support it. But they are not insurmountable.

In our work we have focused on the power of framing—choices we make in how we position issues—to open up more productive discussion about child mental health. We have found a number of strategies that show promise in doing this.

We have found that messages that frame child mental health as a pathway to positive development and wellbeing increase people’s perception of the salience of the issue and their support for policies that address it. This can be as simple as starting a communication with messages about child health, development, and wellbeing and then positioning children’s mental health as a vital part of getting to these outcomes. People already care about the health and wellbeing of Australia’s children; helping them see mental health as a part of this is powerful.

We have also found that taking a functional perspective to children’s mental health helps people understand and get behind the issue.

This means making clear and concrete what positive mental health allows children to do (form relationships, learn, play, deal with challenges…). It is essential in this framing to not only talk about the functional challenges of mental health problems, but to focus on the healthy and positive behaviors and interactions that child mental health enables.

It is important that communications achieve better balance between discussions of positive and negative mental health and avoid the tendency to focus overwhelmingly on crisis and fear about the dangers of mental health problems.

Frequently, discussions of child mental health and child development more generally, focus on the differed benefits created by investments in this early period of life. We see this through the emphasis on ROI (return on investment). Our research has found that, while these future frames can be effective policy advocacy tools, messages are most powerful when they balance this sense of future benefits with discussions of the here and now impacts of positive development and mental health. This means continuing to make points about future benefits but also including ideas about how supporting children’s mental health improves the lives of children and families right now.

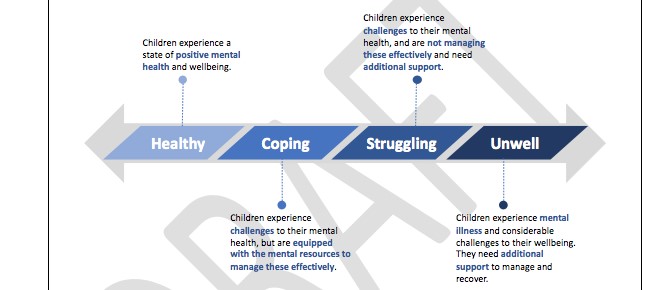

One particularly promising frame, which is being promoted by Centre for Community Child Health,[1] is the idea of a continuum. This is the idea that our mental health—including that of young children—is like a continuum with “healthy” on one end and “unwell” on the other. Between these ends are the positions of “coping” and “struggling”.

[1] Australian Government National Mental Health Commission (2021) The National Children’s Mental Health and Wellbeing Strategy. Draft for Consultation.

This frame encourages understanding of three key points. First, that mental health is dynamic; the position of any one child on the continuum moves over time based on experiences and supports. This combats the deterministic understanding that people have of mental health and sets up the idea that mental health is contingent on our environments, experiences, and relationships.

The continuum idea also sets the functional frame described above and channels people’s thinking towards the things that mental health enables rather than casting mental health as the ultimate outcome. Finally, the idea of a continuum encourages connection and engagement. It provokes people to consider their own state and current position on the continuum, and how they move along the continuum over time. This kind of personal connection is helpful in moving mindsets and shifting thinking.

Applying these and other frames is a key dimension of more equitably supporting the mental health of Australia’s children. We need to use our words and messages to navigate obstacles and unlock space for a more productive and engaged public conversation on children’s mental health and our social responsibility to better support it for all children.

Want to learn more? Be a part of the new framing story by joining in our free e-learning module.

More information about the Core Story for Early Childhood Development and Learning can be found here.

Popular

Quality

Practice

Provider

Research

Workforce

Honouring the quiet magic of early childhood

2025-07-11 09:15:00

by Fiona Alston

Practice

Provider

Quality

Research

Workforce

New activity booklet supports everyday conversations to keep children safe

2025-07-10 09:00:16

by Fiona Alston

Quality

Practice

Provider

Workforce

Reclaiming Joy: Why connection, curiosity and care still matter in early childhood education

2025-07-09 10:00:07

by Fiona Alston