Single parents are getting priced out of daycare, triggering a vicious cycle of entrenched poverty

Female workforce participation has risen for the past two decades in Australia, and in turn, more young kids have been attending formal childcare.

So it’s very surprising the latest Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey shows a steep fall in the use of formal childcare among single-parent households, which by and large are headed by women.

The HILDA Survey has been running since 2001, and the same 17,000 or so Australians are interviewed every year on issues such as health, family and work. The newest report, published today, is based on 2018 figures, the most recent available data.

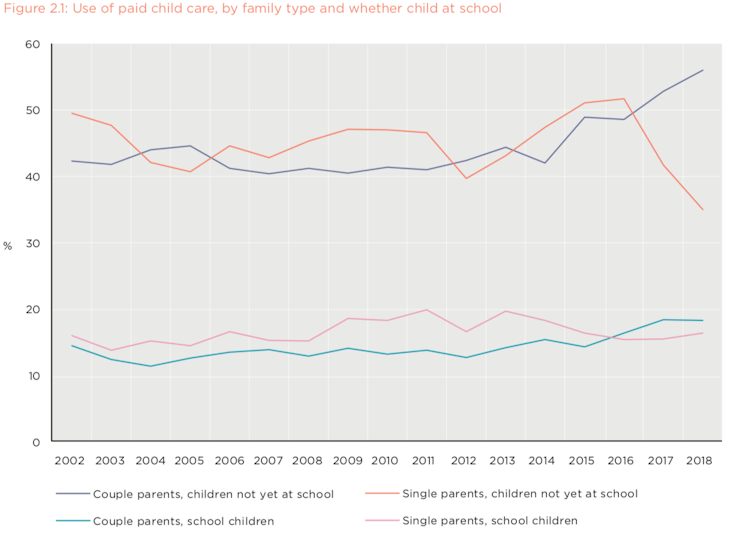

According to the HILDA Survey, 52% of single-parent households with kids aged under four used formal childcare back in 2016. But in 2018, that share has dropped to 35%. The same trend isn’t observed among coupled parents.

While it is unclear what is driving this trend, it is potentially a sign many single parents simply can’t afford formal childcare. If so, it risks kicking off a vicious cycle in which lack of money, lack of childcare, and lack of employment opportunities trap single parents in entrenched disadvantage.

About 52% of single parent households with kids aged under four used formal childcare back in 2016. But in 2018, however, that share has dropped to just 35%.

HILDA 2020

A worrying trend

There doesn’t appear to be an obvious explanation for this phenomenon. The change in usage patterns comes at a time when childcare subsidies had just been substantially increased for the majority of low- and middle-income households, reducing their out-of-pocket expenses.

There also appears to be no reduced need for care; employment levels among single parents remained stable even while childcare usage dropped.

It may be many single parents are instead relying on informal childcare arrangements, such as relatives or friends. The HILDA data reveal a growing number of single parents with kids below school age, who have a job but no formal care arrangement.

In 2018, only 52% of all employed single parents with young kids had a formal care arrangement, compared with an average of 70% over the previous ten years.

This is a worrying new trend. It sets up single parents for a host of logistical problems juggling multiple care arrangements and unreliable access to care, which can jeopardise their employment in the longer term.

And because it’s unregulated, there’s no way to enforce quality standards of informal care arrangements. That could potentially limit children’s social, behavioural and cognitive development if they miss out on formal care.

As in other countries, Australian single-parent families who don’t access formal childcare are the most disadvantaged; they are more likely to live in remote or regional Australia, and in socially and economically disadvantaged locations, and the parents in these families have lower educational qualifications.

There is a strong link between families that don’t or cannot access formal childcare, and families affected by poverty and lack of employment.

A cycle of poverty and entrenched disadvantage

HILDA tracks households over time, so we can also see each family’s circumstances and childcare usage in the year prior. When we analysed single-parent households over time, we found two important facts.

First, the falling rates of formal childcare usage among single parents isn’t just about a shift over time, in which fewer and fewer single new families begin to use the formal care sector when their child is old enough.

It is, to a large extent, about families that already had a formal care arrangement in place, but cancelled their enrolments before their kids reached school age.

And second, just before these families stopped using childcare, they tended to be somewhat poorer than their counterparts who continued to use it — but not as poor as the families are who don’t use childcare in the long run.

In other words, there could be a vicious cycle whereby lack of income (whether because the single parent is unemployed, or employed on a low wage) prompts families to drop childcare, further worsening their economic position down the track because work opportunities are more constrained. It’s hard to maximise work opportunities if you don’t have reliable childcare.

The HILDA Survey had already shown a substantial increase in relative poverty rates among single-parent households — from 15% in 2016 to 25% in 2018, well above the 10.7% overall rate of relative poverty.

Given the devastating effects of COVID-19, we can expect the number of single-parent families that enter a cycle of poverty and entrenched disadvantage will only grow further.

It appears that even after the recent increase in subsidies, our childcare system is badly set up to help them find a way out.

This piece was co-published with the University of Melbourne’s Pursuit.![]()

Barbara Broadway, Senior Research Fellow, Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, University of Melbourne and Esperanza Vera-Toscano, Senior research fellow, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Popular

Economics

Policy

Provider

Workforce

Prime Minister Albanese backs Tasmanian Labor’s childcare plan, highlights national early learning progress

2025-06-30 10:42:02

by Fiona Alston

Economics

Provider

Quality

Practice

Policy

Workforce

South Australia announces major OSHC sector reforms aimed at boosting quality and access

2025-06-30 09:49:48

by Fiona Alston

Events News

Marketplace

Practice

Provider

Quality

Research

Workforce

How do you build and keep your dream team? ECEC Workforce and Wellbeing Forum tackles the big questions

2025-06-24 15:20:53

by Fiona Alston