After Robodebt, it’s time to address ParentsNext

Robodebt isn’t the only measure the government should consider withdrawing.

Late last Friday, after a long press conference from the prime minister which avoided any mention of the topic, the government conceded all points on its so-called “robodebt” formula for alleging welfare recipients have been overpaid.

It’ll refund all of the A$721 million collected including interest charged and collection fees charged. The 470,000 Australians affected have yet to receive an apology or damages.

Our research suggests ParentsNext needs also to be addressed.

It subjects more than 75,000 low-income parents of pre-school children, 95% of whom are female, to a compulsory, complicated and discriminatory “pre-employment program”.

Those deemed not to cooperate lose their parenting payments.

Disproportionately Indigenous and female

Participation is based upon perceived risk of “intergenerational welfare dependency”, itself a questionable assumption.

It began as a trial in ten locations in 2016. From July 2018 it was rolled out across Australia.

In December 2018, 75,259 people were in ParentsNext: 95% women, 19% Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, 21% culturally and linguistically diverse, and 12% with a disability.

Our interviews with participants paint a picture of a weekly “tick-the-box” exercise conducted under the threat of losing payments below the poverty line at a time when caring for children, often under challenging circumstances, is more than enough to keep them busy.

Natasha* left school in Year 10 and has since worked in sales and administration roles. She arranged for a friend to come and keep her two-year-old occupied so she would be free to take a phone call scheduled to determine her eligibility for ParentsNext.

After an hour of waiting, Natasha was stressed and her friend had to leave. Her call came eventually.

Anna’s never did. Anna* has three children and cares for people with spinal cord injuries on a casual basis. Her Centrelink payments were suspended because she was deemed to have missed a compulsory meeting about ParentsNext, deemed to have been set up in a call that never came.

Makework instead of work

ParentsNext attracted negative media attention in late 2018, with women revealing they were forced to sign participation plans agreeing to attend playgroups, story-time sessions at their local library and swimming lessons at their own expense, instead of getting appropriate training and employment assistance.

Failure to sign would have meant loss of income.

Megan* agreed to keep on taking her child to a local playgroup. Once playgroup became a compulsory matter, however, it “drained the joy” from her involvement and she grew increasingly resentful about needing to be there.

Svetlana* explained to her case-worker that most days she catches two buses across town to care for her elderly mother. This responsibility was not deemed a legitimate activity. She has health problems and is a single mother with few social connections.

“I need help,” she said simply. Like others, she had hoped ParentsNext would help get her back into the workforce. She was left demoralised after agreeing to enrol in an online TAFE course that proved too difficult to complete.

Meanwhile, program providers profit from creating and enforcing participation in “activities” of debatable benefit to participants.

These kinds of revelations led to a Senate Inquiry that reported in March 2019.

ParentsNext circular

ParentsNext continues largely unreformed despite the Senate committee’s recommendation that it cease in its current form.

It is consistent with a long Australian history of blaming, punishing and stigmatising welfare recipients and single mothers in particular.

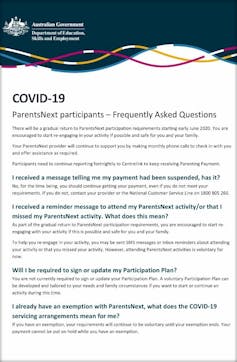

Participation requirements have been suspended during the stay-at-home period of COVID-19 restrictions, allowing participants to focus on parenting, but they are about to restart.

We can do better than forcing already stretched parents into more stressful situations. They already do huge amounts of unpaid work caring for their children.

This unpaid work is a fundamental part of economy; by some estimates worth three times as much as our mining, finance, construction or manufacturing industries.

We ought to value the role of unpaid care and view it as an irreplaceable component of the formal economy, essential to our rebuilding post-COVID.

*Pseudonyms have been used for the people taking part in our research

Andi Sebastian and Jenny Davidson (Council for Single Mothers and their Children) also authored this article.![]()

Elise Klein, Senior Lecturer, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University and Eve Vincent, Senior Lecturer, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Popular

Quality

Practice

Provider

Research

Workforce

Honouring the quiet magic of early childhood

2025-07-11 09:15:00

by Fiona Alston

Policy

Practice

Provider

Quality

Workforce

Minister Jess Walsh signals urgent action on safety and oversight in early learning

2025-07-11 08:45:01

by Fiona Alston

Workforce

Policy

Quality

Practice

Provider

Research

The silent oath: Why child protection is personal for every educator

2025-07-17 09:00:31

by Fiona Alston