Advocacy

Research

Hearing health crisis among Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islanders

Freya Lucas

Apr 29, 2019

Save

The high prevalence of ear disease among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders is linked with poor education and social problems, writes Professor Cath McMahon, who is dedicated to transforming hearing health in indigenous communities.

Middle ear disease – or otitis media (OM) - is considered by the World Health Organisation (WHO) to be a massive public health problem in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.Australia lacks national prevalence data, however, estimated rates suggest that the prevalence of OM is as high as one in five children aged between newborn and four years, increasing to one in two in remote communities in Northern and Central Australia.

Compared with the non-Indigenous population, OM occurs earlier, more frequently, and is more severe. Medical interventions, such as ongoing antibiotic prescription, vaccination programs, and health check programs have limited effectiveness and need to be reconsidered.

The hearing loss which results is associated with poorer educational outcomes, social and behavioural problems, and contributes to the over-representation of Aboriginal people in the criminal justice system. While significant investments have been made to address this major health inequity in Australia, the prevalence of OM and its negative impacts on the individual and society has not substantially changed since the 1970’s, and existing solutions are not meeting the unique needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander society.

Rethinking how we approach this problem is critical - we need to accelerate our efforts to make exponential improvements towards closing the gap in hearing health, and direct them towards solutions that are effective for the community.Taking a public health approach will enable the development of sustainable initiatives within this population, where social determinants of health drive the wide and sustained disparities in hearing health. Core components are to understand the community for whom solutions are being designed; their priorities and conceptualisations of health.

For example, while ear and hearing care may not be a priority, designing solutions at a community level ensures that a care pathway can be embedded into existing systems and processes and accordingly prioritised. A community-based approach takes into account whether solutions are culturally appropriate, implementable and sustainable – whether antibiotics can be refrigerated and how accessible nutritional food such as fruit and vegetables is for the community.

A public health approach prioritises the development of a national ear and hearing care strategy that involves the whole of government, local communities and businesses, society, and organisations which can advocate for and support widespread implementation. Policies and programmes must extend their reach beyond the health sector, to encompass housing and education sectors.

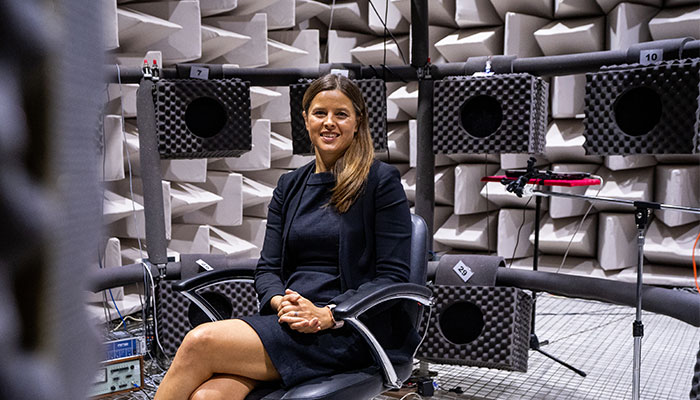

Challenge accepted: Professor Cath McMahon is calling for a halt to hearing loss among indigenous people through health and service partnerships with affected communities.The effectiveness of implementation must be measured by changes in the prevalence, incidence and impacts of the problem. Importantly, any solutions must be co-designed with the community, and they must be empowered to manage their own health, as individuals, families and communities are all connected.

Challenge accepted: Professor Cath McMahon is calling for a halt to hearing loss among indigenous people through health and service partnerships with affected communities.The effectiveness of implementation must be measured by changes in the prevalence, incidence and impacts of the problem. Importantly, any solutions must be co-designed with the community, and they must be empowered to manage their own health, as individuals, families and communities are all connected.Recognising the impact of colonisation, the need for self-determination, and the core values of respect and cultural integrity are important to the design of implementable and sustainable solutions. At the individual level, the high rates of smoking, poor nutrition and hygiene must be addressed.

Deep listening. It's very embedded in our culture, not just as a Yaegl/Bundjalung person, but right across our nation. If there is a problem with hearing, kids are not learing this process of deep listening and connecting to the land and feeling the country.- Dr Liesa Clague, PhD and Yaegl/Bundjalung/Gumbaynggirr womanEnsuring access to good quality housing, clean water and sanitation is critical and a basic human right. Multi-morbidity is not uncommon and similarities exist in the approach needed for ear problems, vision problems and cardiovascular problems.

Yet, disease-based approaches to addressing these challenges exist, therefore, considering a single holistic approach under a broader conceptual framework of health will lead to solutions that can be embedded and governed at a community-level. Health in such communities is a complex issue, which requires the need for complex approaches to solutions.

Macquarie University has global reach in hearing health, through collaboration with the World Health Organisation and with representation on the recently announced Lancet Commission on Global Hearing Health.

It also has local reach, driven through the Australian Hearing Hub, which is a collaboration and engagement across academic, clinical and rehabilitative services, manufacturing and community advocacy sectors in hearing health, to drive impact across the sector. With the Hearing Strategy 2030 released on March 18th 2019, Macquarie aims to transform hearing health by leading the development of a national approach in ear and hearing care in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations.

Professor Cath McMahon is the Director of Audiology and Director of H:EAR (Hearing, Education, Application, Research) at Macquarie University.

This article has been republished with the permission of the Macquarie University Lighthouse.

Don’t miss a thing

Related Articles