A Tale of Four Cities – a comparative AEDC analysis

opinion

The views expressed by contributors are their own and not the view of The Sector.

By age five, around 300,000 children are starting school, but more than one in five children are not as prepared as their peers, says Megan O’Connell, Honorary Senior Fellow, Melbourne Graduate School of Education and Director of Megan O’Connell Consulting in presenting her analysis of the recently released 2018 Australian Early Development Census (AEDC) data. The information shared below with The Sector outlines Ms O’Connell’s interpretations and perspectives.

In presenting as developmentally vulnerable in one or more domains, Ms O’Connell said that children may not have the language or communication skills they need to express themselves, and are increasingly struggling to regulate their emotions, to play alongside their peers and to build the physical stamina needed to sit in class, to use scissors and to participate in sport.

In every community, there are children who are starting school developmentally behind others, but the odds of being behind – or developmentally vulnerable in one or more domains – vary dramatically depending on gender, indigeneity and where they live. So, too, does a child’s access to services.

Measuring vulnerability

The AEDC commenced in 2009, and is repeated every three years, providing interested community members and educational practitioners with an overview of the development of children in their first year of school against five areas known as domains – physical health and wellbeing; social competence; emotional maturity; language and cognitive skills; and, communication skills and general knowledge.

To determine a child’s position within the band of each domain, teachers answer a series of questions based on their observations of the children in their class. The answers are tallied and children are given a score from zero to ten in each of the domains, before being categorised as ‘on track’, ‘at risk’ or ‘developmentally vulnerable’ based on a series of cut-off scores developed for each domain in 2009.

How is the data used?

Schools, communities and governments use AEDC results to target initiatives to reduce developmental vulnerability, with a variety of research linking the AEDC to future wellbeing and education outcomes, Ms O’Connell explained.

With the AEDC now being conducted four times, Ms O’Connell said, there is sufficient trending data to demonstrate changes in the level of developmental vulnerability in Australian children over time.

Trends in how children are faring

Since 2009 the level of developmental vulnerability for Australian children has fallen, with children who are developmentally vulnerable on one domain moving from nearly one in five to over one in four – from 23.6 per cent of children to 21.7 per cent of children – whilst vulnerability on two or more domains has fallen from 11.8 per cent to 11 per cent.

Examining the domains within the AEDC longitudinal data, Ms O’Connell said, reveals a more complex picture of early childhood development. Whilst there have been strong improvements in the development of language, cognitive skills, communication skills, and general knowledge over time, social competence and physical health and wellbeing have marginally worsened. Emotional maturity has fluctuated over time.

Each of the domains is important to children’s development, so while children improving in language and communication skills are important, the decline in social competence, and physical health and wellbeing is concerning, Ms O’Connell said.

Location

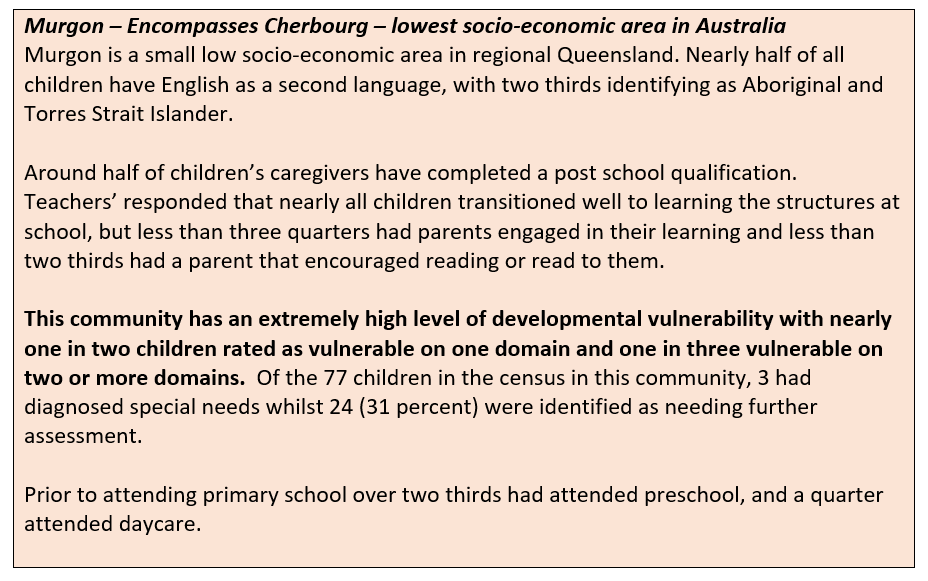

Children who are born further from metropolitan regions are less likely to have their additional health and development needs identified before school and are less likely to participate in a range of early learning experiences more accessible in inner city areas, Ms O’Connell said.

Who is more likely to be vulnerable?

More than 60,000 children per annum are developmentally vulnerable, with vulnerability affecting all suburbs and family groupings. That said, Ms O’Connell’s interpretation highlights that some children and communities fare worse than others, including:

- Boys – 80 per cent more likely to be vulnerable than girls

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (ATSI) – more than double as likely to be vulnerable than non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children

- Lowest socio-economic background – more than double as likely to be vulnerable than children from the highest socio-economic background

- Very remote areas – more than double as likely to be vulnerable than children from major cities.

A tale of four cities

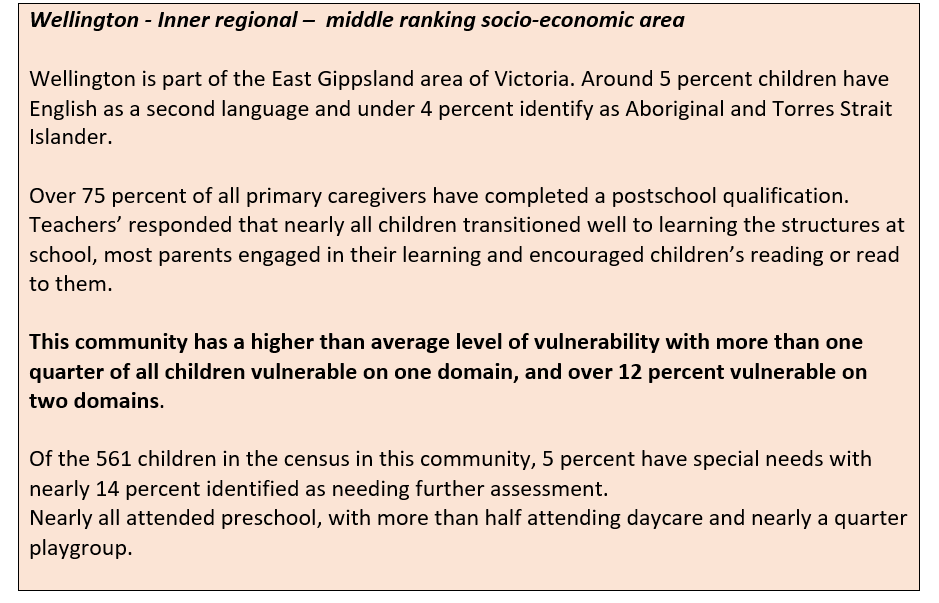

By examining four communities around Australia, the comparisons become clear, with the results showing large differences in community demographics, parental engagement in education, and access to educational and support services.

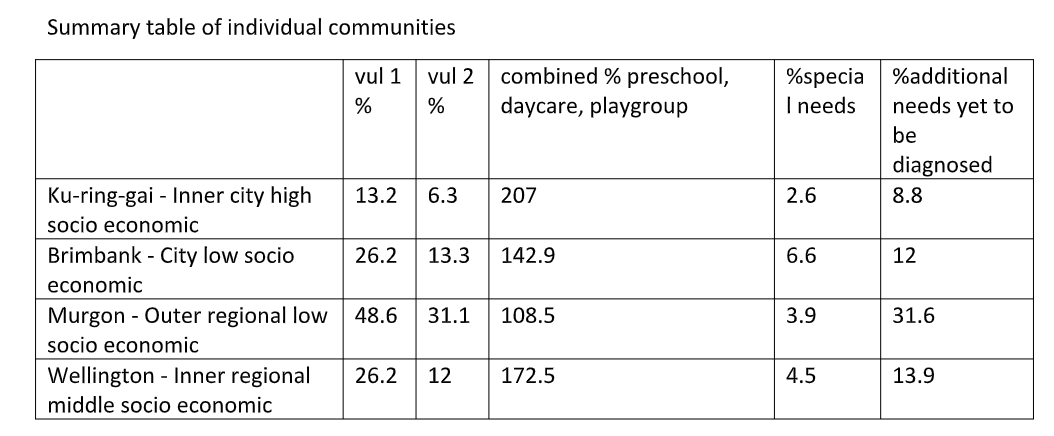

The results, Ms O’Connell says, highlight the areas that need further government and community attention to prepare all children for a life of learning. The table below provides a summary of the data covered in the case studies.

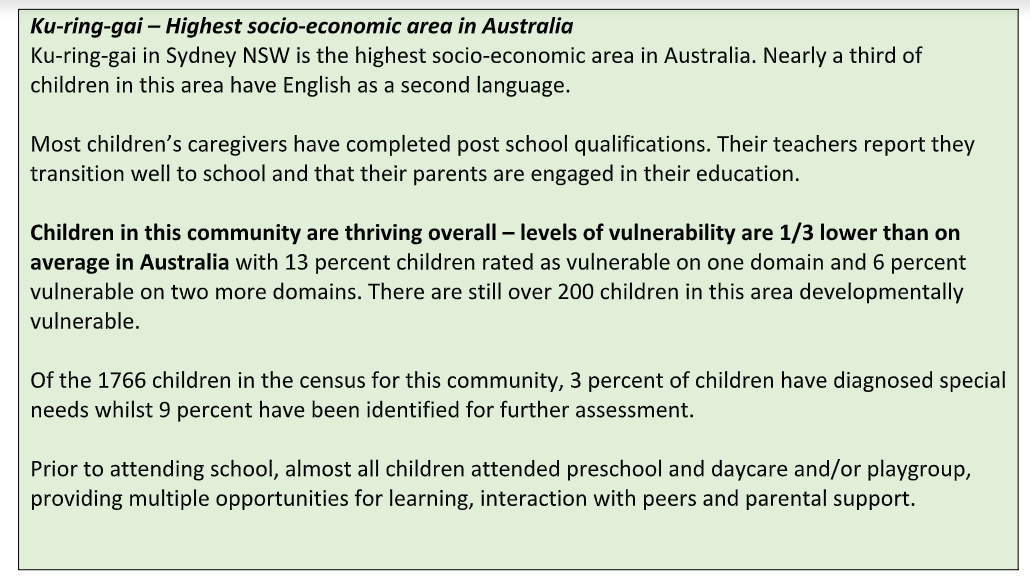

The differences between the highest socio-economic community in Australia, Ku-ring-gai, and the lowest, Murgon, are stark. Children in Murgon are nearly four times more likely to be vulnerable, and are accessing early learning, at nearly half the rate of children in Ku-ring-gai. Nearly a third of children have health and development needs that are yet to be diagnosed.

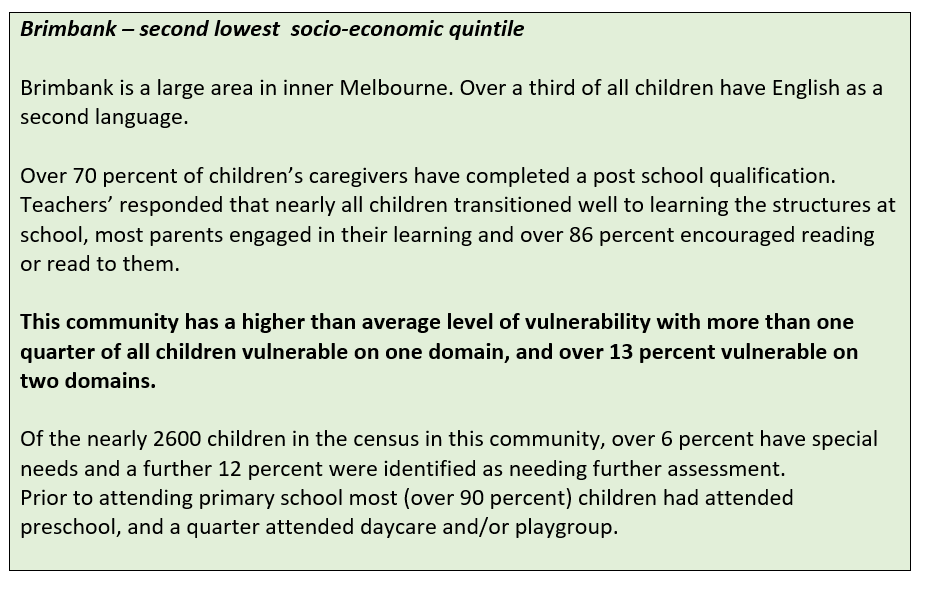

Looking at other communities you can see differing levels of participation and vulnerability, from a vulnerable inner city community to a more affluent but equally vulnerable regional community, Ms O’Connell said.

“This data shows us that all children need access to quality early childhood experiences to support parents and families, including access to early intervention services.”

The case studies provide greater detail on the communities in question followed by a consideration of what can be done to improve outcomes for all children.

Conclusion and recommendations

The data shows that children born closer to cities, in higher socio-economic communities, are less likely to become developmentally vulnerable. While children in higher socio-economic areas are more likely to fare better, the effects of living in a rural or remote community temper the advantage – partly because children close to cities are more likely to attend a combination of learning experiences such as preschool, playgroup and long day care.

The data from the case studies shows that, where children had engaged in more early learning, parents were more engaged when children entered school. For some families, additional support from when children are young is needed to build their capacity and support the growth of a strong home learning environment. This help can also identify the need for assessment for some children.

A high number of children have undiagnosed needs that are likely to make learning more challenging if unaddressed. Early intervention is vital for children with special needs, yet nearly 40,000 children need further assessment in their first year of school. Many of these issues could have been identified during the first five years, placing the children in a stronger position to start school.

These issues could be addressed through universal platforms such as maternal and child health and early childhood education and care.

Studies such as Right@Home show it is possible to positively influence the home learning environment and to identify children who may require additional support in key areas such as language and communication.

Quality early childhood education plays a strong role in helping to identify and address emerging issues for children before they start school, linking children and carers to the support services they need. At least two years of quality early learning before school is needed for all children and for vulnerable children earlier access could help to identify and address emerging health and development needs.

There is an urgent need, Ms O’Connell said, for the incoming Federal Government to address inequalities faced by children and families.

“It is not right that where a child is born, either distance from city or level or economic advantage, dictates their destiny. We need an approach to identify and assist vulnerable families from early on, and provide all children with the help they need so they can start school ready and thrive,” Ms O’Connell said.

Popular

Practice

Provider

Quality

Research

Workforce

New activity booklet supports everyday conversations to keep children safe

2025-07-10 09:00:16

by Fiona Alston

Quality

Practice

Provider

Workforce

Reclaiming Joy: Why connection, curiosity and care still matter in early childhood education

2025-07-09 10:00:07

by Fiona Alston

Policy

Practice

Provider

Quality

Research

Workforce

Beyond the headlines: celebrating educators and the power of positive relationships in early learning

2025-07-07 10:00:24

by Fiona Alston