Jobs News

Legislation

Policy

Workforce

A mandate for multi-employer bargaining? Without it, wages for the low paid won’t rise

Freya Lucas

Nov 14, 2022

Save

“The fact is that the government that I lead was elected with a mandate to increase people’s wages,” Prime Minister Anthony Albanese told the House of Representatives last week, as parliament debated the government’s bill to increase access to multi-employer collective bargaining.

The bill passed the lower house last Thursday, after the government made changes that Employment Relations Minister Tony Burke said would ensure the “primacy” of enterprise bargaining. Further concessions may be needed to pass the Senate.Employer groups argue the multi-employer bargaining provisions could return Australia to a 1970s-style system with high levels of industrial conflict. They claim it will lead unions to use sector-wide industrial action to achieve their goals.

Importantly, the Council of Small Business Organisations of Australia, which supports multi-employer bargaining in principle, has ended up opposing Labor’s provisions, saying they make the system more complex.

Nonetheless, Albanese has a point about Labor having a mandate.

He never made an explicit promise to expand multi-employer bargaining. He didn’t campaign on it. But he did promise to lift stagnating wages – particularly for those in low-paid, feminised sectors – and his government cannot deliver on that without fixing a broken industrial relations system.

Provisions already exist

Multi-employer agreements are, in fact, meant to occur now, under the Fair Work Act passed by the Rudd Labor government in 2009.The act empowers the industrial relations umpire (known as Fair Work Australia until 2013, now the Fair Work Commission) to authorise multi-employer bargaining in sectors where employees are low-paid and “have not had access to collective bargaining or who face substantial difficulty bargaining at the enterprise level”.

The Rudd government included these provisions – known as the Low-Paid Bargaining Stream – because of the evidence that wages and conditions in areas such as child care, aged care, community services, security and cleaning had stagnated under single-enterprise bargaining.

Workers in these areas were disadvantaged by a range of factors. There were high rates of casual and part-time employment. Many employers were small or medium-sized, with limited resources and skills for bargaining.

In child care and aged care, wages were effectively set by a third party – the federal government, the main funder of services. Care workers were also more reticent to strike as part of the bargaining process, because of the effect on clients.

But they just don’t work

In 12 years of the Fair Work Act, however, its multi-employer provisions have not led to a single bargain.This is because the legislation requires the Fair Work commissioners to take into account complex considerations to determine if multi-employer bargaining is in the public interest.

A 2011 application by the Australian Nursing Federation to bargain with general practice clinics and medical centres was rejected on the grounds nurses were not low-paid.

A 2014 application by the United Voice union to bargain with five security service employers in Canberra was rejected because three employers already had enterprise agreements.

Just one attempt has passed the first stage of obtaining authorisation. In 2010, United Voice and the Queensland branch of the Australian Workers’ Union sought authorisation to bargain on behalf of 60,000 workers with residential aged-care providers funded by the federal government. This was about 300 employers.

Fair Work Australia agreed, but also excluded workplaces that had previously made an enterprise agreement. This knocked out about half the employers, undermining the collective strength needed to get the federal government to agree to fund any wage increases.

Whatever the merits of arguments over details in the government’s proposed bill, there should be no argument that the system needs reform.

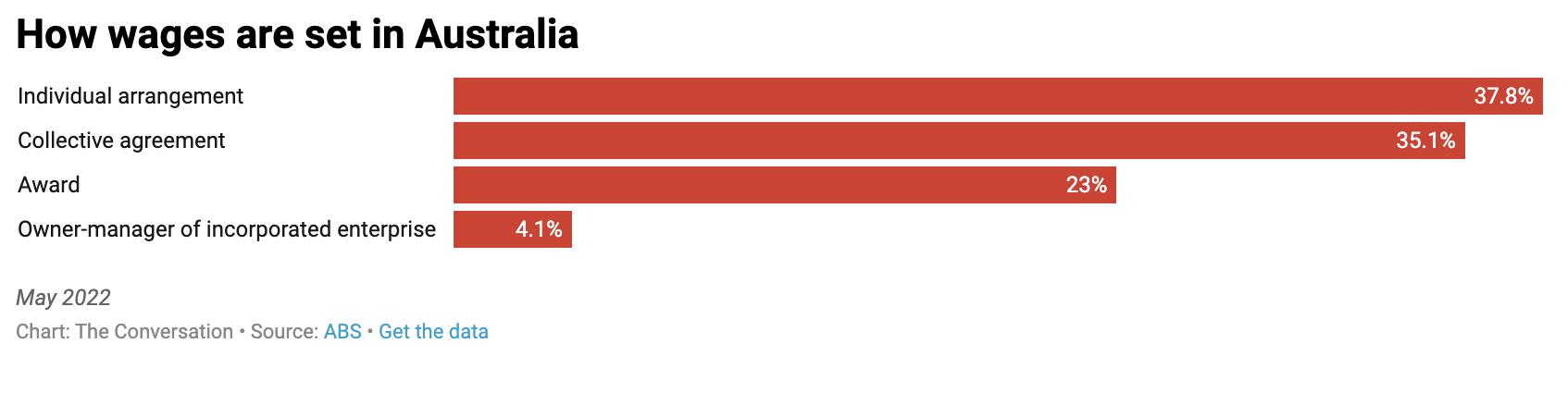

Enterprise bargaining hasn’t delivered. Collective bargaining has become the exception rather than the norm. Over the past decade the share of the workforce covered by an enterprise agreement has halved, to 12% of all employees.

Greater access to multi-employer bargaining is needed for fair wages and conditions for many employees, especially those in low-paid feminised sectors where staff shortages and high turnover are widely recognised to be threatening care quality and jeopardising the sustainability of the industries.

Fiona Macdonald, Policy Director, Centre for Future Work at the Australia Institute and Adjunct Principal Research Fellow, RMIT University, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t miss a thing

Related Articles